(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Dear Readers: This post is not typical. This is about my struggle with depression in Massachusetts. Thanks for following! -Cindy ❤ I usually was not an excessive worrier. The crippling anxiety I experienced earlier, after Beth’s spinal cord injury, had been triggered by guilt and deadly health risks. When I lived near Harvard, I worried only a bit about all my children, and general things like them finding meaningful work and a loving partner. Maria and Ben had significant others; however, my youngest felt no rush to date. She had a very full plate. Both of my girls thought it appalling that I had married one week before my nineteenth birthday, much too young in their minds. We had no way of knowing that Beth’s first steady boyfriend lived across Harvard Yard in another freshman dorm, or that they would not meet until graduate school in another state. At the end of the school year, my mood plummeted quickly after I gradually discontinued Zoloft. I banked on my body adjusting over time, and it did, but not in the direction I hoped. At the same time, my roommate Janet left for Ohio to be married, which meant I needed to move out of the apartment before her honeymoon ended. For the month until the school year finished, when I would drive home to Ohio with Beth, I arranged to sleep on a sofa bed in a Coop friend’s apartment north of campus. On my moving day, I woke up to an alarming new low, exacerbated by a piercing, throbbing headache and a flare of intense fibromyalgia. I relied daily on Celebrex, an anti-inflammatory medicine, to reduce the headache. Unfortunately, the maximum dose couldn’t reach this higher level. Over-the-counter pain drugs didn’t work for me, and I had a bad reaction to opiates, so there were no good pain options. Deep sadness stung, mentally and physically. Every small thing seemed much too difficult. I forced myself to go through the motions for my morning personal care assistant job, barely saying a word and wiping tears away discreetly. After, I trudged through the thirty-minute walk from the Quad to my apartment on auto drive. I passed through the tiny apartment for the last time to take the garbage out, my steps creaking on the uneven floor. Janet bought my bed, and I left her my lamp and the bedding. When I pushed my key under Janet’s door, I carried my duffel, the same one I moved in with eight months earlier. I left the duffel in the trunk of the car. I had the day off from the Coop and planned to move into my temporary housing that evening. I stood at a corner, overwhelmed by sadness and the simple choice of which street to cross. And the idea of moving to a friend’s apartment where I’d never been before. The sunny day colored in despair, carrying me back to my old guilt and regret. I couldn’t stop crying. I felt weak and worthless. Frustrated and embarrassed, I decided not to reach out to John, or anyone. I didn’t have anywhere to go, no bed to curl up on, so I rode the T into Boston with the plan of hiding in a movie theater while I regained control. Instead, I paced in the expanse of the Boston Common, trying to calm down enough to call my friend Bonnie. I told her I’d move in the next day instead of that evening. I walked aimlessly, not caring how I looked. Far from home, I didn't know anyone in Boston. Even in tears, I certainly wasn’t the strangest sight in the Common on that or any other day. Next: Depression and Hope!

14 Comments

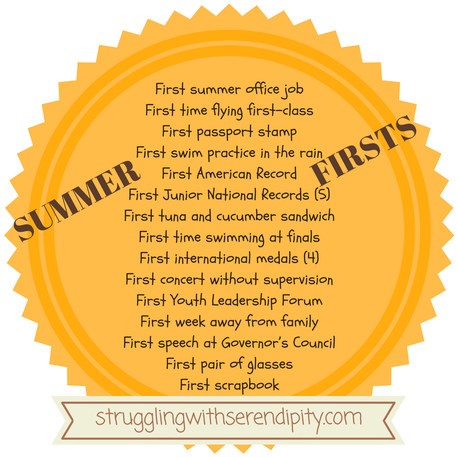

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) I stopped counseling since I was perfectly fine. After all, I finally made progress in the wake of three years of weekly sessions. Guilt and anxiety no longer dominated my days, which felt like a monumental gift. I scheduled dentist appointments to fix my second cracked molar, casualties of teeth clenching—despite the biteplate I wore each night. My doctor added a temporary muscle relaxant at bedtime to reduce the clenching. A high dose of Celebrex usually tempered the headache and kept me moving. I watched Beth hold a pen awkwardly in her right fist, not hesitating as she wrote her motto on a Challenged Athletes application. ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE. She wholeheartedly believed the motto was true. And it really was, though only for her and a small percentage of other people with her priceless perspective. Those with and without a disability. I filed away a note to myself that said, “Anything is possible, except when it’s not.” I intended to write about how she dismissed all she couldn’t do as irrelevant. “I think walking is over-rated,” Beth said, with a smile. Unable to stand and not focused on a far-off cure for quadriplegia, she continued to work hard to defy the usual limits of quad hands. Her spinal cord injury erased normal finger function. Even so, she wouldn’t write off any fine-motor tasks she really wanted to do. One example of many: putting her hair up in a ponytail after trying several times a day for two years. A tribute to unwavering belief and persistence. As Beth's last year of high school started, she quietly completed an early admission application to Harvard, convinced it was a long shot. “I didn’t tell anyone since I didn’t think I would get in,” she said. If someone asked about college plans, Beth mentioned the University of Michigan, one of the colleges she planned to apply to after she heard back from Harvard in December. NEXT: A new job!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) College applications covered our kitchen table before Beth’s senior year of high school began. She questioned the need for help at college her freshman year and wondered if I could live off-campus instead of in the dorm with her. Separate housing for me for any amount of time would add costs on top of her out-of-state tuition, room, and board. High college expenses seemed certain. John and I decided not to hold her back because of finances. We owned the Tiffin house and planned to borrow off it. My second counselor moved away and the third nudged me forward. After nearly three years of weekly sessions, I had few tears left. I had been spinning in a rut, perseverating on my choices the night of Beth’s injury. As if I had a replay option. The new psychologist told me the accident could not have happened any other way. She framed it as less of a colossal failure and more of a perfect storm of events. I woke up very early that morning to set up a refreshment stand for the choir contest. John stayed home to study for his National Board test. The night of the accident, the OSU concert ran longer than expected. The psychologist’s next point hit home: I could not make a good decision (i.e., calling John on the pay phone), because exhaustion impaired my judgment. That fact somehow flipped a switch for me and allowed a measure of forgiveness. However, no amount of reasoning would be enough, if Beth had been unhappy. I gradually reduced my zoloft to a lower dose. As always, my headache tightrope remained, a precarious and somewhat mysterious balancing act to keep the level manageable. At home, Beth gathered summer mementos and made colorful collages with a small paper cutter. She used markers to add descriptions and funny comments on each page, approximating the calligraphy style she learned before her injury. She created a tribute to the magical summer in her first scrapbook. The last page listed 15 notable summer firsts, including her first US Paralympics American Record, her first passport stamp, her first tuna fish and cucumber sandwich, her first concert without a parent, and her first swim practice in the rain. Beth’s very best ‘first’ of the summer: wheeling around Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) On a free day, Beth suggested the Mohegan Sun casino to see the immense works of art. Wheeling through massive spaces, she realized at one point that we had accidentally entered a restricted area for adults eighteen and over. With slot machines nearby, Beth, seventeen, asked to try the poker slots. I put quarters in the machine and let her tell me which cards to keep. She never touched the slots and helped me lose $30. I took photographs at every destination while Beth collected menus and flyers and other small things for a scrapbook she planned to make. She found one she liked at a shop in the historic bridge district in Mystic, Connecticut. Equally exciting, we found the fifth Harry Potter book, The Order of the Phoenix, to add to her collection, one of the five million copies bought in the first 24 hours. Beth’s happiness was contagious. We ate lunch at Mystic Pizza, famous for the 1988 movie with the same name. I helped her scoot out of her chair to a seat in a booth. Memorabilia decorated every nook and cranny at the restaurant and Beth rated it the best pizza, ever. I bought her “A Slice of Heaven” T-shirt. We sat on the waterfront of Mystic’s picturesque harbor on a flawless afternoon. An easy travel buddy, Beth appreciated everything under the sun. She tilted her face upward, closed her eyes, and smiled. I wrapped her in a big bear hug. She patted my back with her right hand, a habit from her toddler days. Knowing how suddenly bad things could happen, I would never take joy for granted. I embraced the singular moment while a new realization dawned. My guilt for causing her injury was self-imposed and no one, least of all Beth, blamed me. Junior Nationals ended with a dinner and dance in a large packed ballroom. When loud music started, hundreds of kids with every kind of physical disability danced standing up, sitting in a wheelchair, or break dancing on the floor. With no one different and no one the same, they all shined in that snapshot of time. Beth danced carefree in the middle of it all. Next destination of a non-stop summer: Cambridge, Massachusetts! (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Two and a half years after Beth’s spinal cord injury, I expected a gradual catharsis with my weekly counseling. But sessions still only stirred up tearful regrets for causing the accident. I thought that I must be doing something wrong, that I failed at therapy. After, I sat in the car, breathing deeply, until I carried no visible baggage home. I scheduled more appointments, hoping to find the person I had been before the accident. I was determined to redeem myself with Beth, though others needed me, too. And I needed them. I was intensely grateful for the people in my life. I wished gratitude could cure anxiety. Trying to look normal was a challenge on days when worst case scenarios dominated my thoughts. I had to concentrate to pay attention, even with my immediate family, though there was no lack of love or genuine interest. Unlike Beth, I had no grand goals. What I basically wanted — after magically erasing Beth’s injury — was the absence of pain. No headache that ebbed and flowed. No guilt and depression. No anxiety that also ebbed and flowed. Some days, Beth emanated vulnerability, a lifelong quad perpetually haunted by scary health risks: autonomic dysreflexia, serious infections, bladder stones, blood clots, and pressure sores. On other days, she looked to me like the happy and healthy teenager that she actually was. As a high school junior, Beth never saw the need to say no to extra activities. On top of AP classes and too much homework, she volunteered for fundraisers with the Raptors and for community events with the National Honor Society. She wrote for the school newspaper and worked on the yearbook. She followed her brother’s lead and earned a spot on the Quiz Bowl team. Her specialty: literature. A doctor also asked her to exchange emails with another teenager with a new spinal cord injury. Beth needed me less often, but I was there when she did. At the YMCA pool, on her forward motion quest, she progressed to spending more time with her head above water than under it. I read a book again while I sat on the bleachers, instead of watching every minute. One evening, she finished a backstroke lap as her high school’s swim team arrived to practice. As a few friends stopped to say hello to her, their head coach, Peggy Ewald, introduced herself to Beth... A fortunate accident. Serendipity.  Beth as a toddler :-) Beth as a toddler :-) (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Beth’s first swimming summer ended with her first Sectional meet in August of 2002. When we drove through Indianapolis to Indiana University, we noticed the unusual billboard again, the same one we saw in Seattle. Quadriplegia at Harvard: A+. Sectionals was another packed to the hilt USA Swimming meet. “A swimmer who uses a wheelchair," Beth said, "is still an unusual sight at most swim meets." Able-bodied swimmers stood on the raised blocks to begin races for all the strokes except one: the back, which always started in the water. Most used their feet and legs to surge off the wall. Beth tried to gain a bit of momentum with her hands pushing off the wall. With rare exceptions, backstroke swimmers alternated their arms simply because it was faster. For Beth, the double-arm backstroke resulted in a better time, despite her head dipping under. She improved slightly on her swim times, but aimed higher. When her junior year of high school started, Beth scheduled a GTAC practice late afternoon every Friday. With the Toledo pool filled to capacity, she learned how to share a lane while a coach supervised her backstroke laps. At the end of every practice, she tried to get out of the pool by herself. Beth pressed her back into a corner of the pool and put her hands up on the ledge behind her, to try to lift herself up and out of the water. She rose just a few inches before falling forward, but she kept trying, regardless. Every practice. In addition to swimming on Fridays in Toledo, Beth asked to go to our Tiffin YMCA with me once or twice a week. I helped her into the water. Her practices without a coach focused on forward motion, the first step in her plans to master all of the swim strokes. I watched her closely from the deck bleachers, since she spent more time under water than above it. She somehow could get herself almost to the halfway point of the 25 yard length with a few short bursts to the surface for rapid breaths. Then she had to give her arms a break and roll onto her back to breathe more deeply. Even if by some miracle she could progress continuously on her stomach for the whole length of the pool, a bigger hurdle loomed: learning the mechanics of the butterfly, breaststroke, and freestyle, with legal modifications for legs that dragged behind and hands that could not cup the water. I worried. And worried. Would failing to achieve this goal tip Beth over the edge to depression? And without her buoyant optimism, how would I be able to move forward? Guilt and anxiety plagued my days and nights. What if overused antibiotics lost their effectiveness? That was how the quad in Green Springs had died of pneumonia in the hospital room next to Beth’s. Or would a blood clot travel to her heart or brain? I was sadly stuck in worst-case scenarios. Thankfully, Beth was not. “My next goal is to make the U.S. National Team that will attend the 2004 Paralympics in Athens, Greece.”  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) During Beth’s first summer vacation at home with a spinal cord injury, she focused on time with friends. We rode with another mom in her van full of excited teenagers to an N’Sync concert in Michigan, with the words “PopOdyssey N’Sync” in bright paint on the back window. Near Detroit, a traffic jam on I-75 turned into a party. Girls blared music, waved signs, and shouted to each other across the highway lanes. That might have been fun except for temperatures in the 90’s with high humidity. The van had no air conditioning and there was no breeze as we inched along. Beth flushed with fever, her body unable to sweat to cool down. I carried Tylenol, but nothing to drink it down with since we didn’t anticipate the traffic jam. I encouraged her to take it without water, but she wanted to wait. Approaching the stadium, I frantically waved the handicapped-parking placard out the window at the traffic cop to avoid another jam of cars. Finally parked, I hurried Beth out of the van to the first drink stand for cold bottled water. She took the Tylenol and drank extra water before we found our seats. In shade, Beth felt better before long and danced with her friends. They watched Justin Timberlake, the 20-year-old who stole the show in the pulsing lights on the stage. Our summer comings and goings confused Beth’s high-strung African Gray parrot. He plucked out feathers and injured his skin. A vet put a plastic cone around his neck, making him more miserable. We wondered if Timber had been taken from his parents too soon, and a friend recommended a bird sanctuary in Cleveland. Whether it was my fault or not, the parrot toddler needed more help than we could give. I drove him to the sanctuary, which included an extensive outdoor aviary with dozens of birds. Beth and I cried when we said goodbye to Timber, but we were glad to hear that he recovered quickly, delighted in his new home. Early on an August Saturday, firemen lifted Beth in her wheelchair onto a boat at a Sandusky pier on the Lake Erie shore. I skipped the fishing part of the Fishing Without Boundaries event. When the boats returned, I heard about how Beth caught more perch and walleye than her dad. The boat’s young first mate watched three fishing poles and handed one to her whenever he had a nibble. She reeled in about two dozen fish and let someone else take the fish off the hook. A friendly crowd gathered for a picnic near the docks. A mom told me how children at school made fun of her daughter, who grew up feeling like a victim. A dad shared his ongoing battle with pressure sores, reminding me of an article I read about a woman who had both legs and part of her trunk amputated because of pressure sore infections. Surrounded by the perspective of significant disability, I understood the mental argument that I should be happy and grateful. I was grateful. I could get through most days without crying, and yet... ...part of me sludged through guilt that felt like grief. ...through depression and anxiety that made me afraid of the future. Catastrophes seemed to be waiting in the wings, for Beth, for me, for the rest of our family, for our friends, and for the world. I listened to Beth laugh with the other teenagers and wondered if she could avoid depression entirely.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) The high school’s Individual Education Plan for Beth focused on access: special desks, leaving class early, the private locker room, and getting down the steps during fire drills. At an IEP meeting, the principal asked her what she needed. She surprised me by requesting a place for her wheelchair in the student section of the stadium for home football games. She also mentioned the problem of others being too helpful. When someone grabbed a push handle on the back of her wheelchair, she reached around and lightly smacked their hand with her fist. “I realized that my biggest challenge would be to insist on doing things myself and to become independent again,” Beth said. “At the risk of sounding corny, people are generally kind, so it was my responsibility to speak up for myself.” The first anniversary of the accident came and went without discussion. It didn’t seem to phase Beth, other than an appreciation of how far she had come since then. At counseling, I rehashed the night of her injury. My guilt and anxiety were far from rational and out of my control. Certain that I had ruined Beth’s life, I needed a way to erase the injury and her losses. I wanted nothing less than the world at her fingertips, with hands and legs she could feel and move. With a cut spinal cord, the only chance of recovery would be medical miracles of the future, but I still couldn’t accept her injury—or my role in causing it. The annual regional choir contest had been at Tiffin Columbian on the day Beth was injured on May 20. Early that morning, I had set up the concession stand in the cafeteria. After my girls sang, we left for Columbus. A year later, the choir contest would be out of town. The director, Curtis King, complained when a handicapped-accessible school bus would not be available, but Beth didn’t mind driving with me. I brought a book along and opened it to discourage other parents from talking to me. I also perfected the art of hovering at a distance to be available to Beth, but out of the way. She sang with her 9th grade choir and Maria had a solo in the Women’s Chorus, all earning high marks, as usual. Without being asked, Mr. King and his father had built a portable ramp for the risers so Beth wouldn’t be the only choir member on the stage floor. His unexpected kindness would be repeated by many in other times and places.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Beth's young African Gray parrot screeched and squawked in an impressive range of piercing, demanding sounds. I tried to give Timber attention when he wasn’t yelling at me, but he didn’t like my attempt at a behavior plan. The parrot woke up early every day, an impatient alarm clock. On weekends, John and I took turns babysitting so the girls could sleep in. During my turn, Timber sat on my shoulder while I folded clothes or cleaned or cooked or rewrote my to-do list. I couldn’t sit still. Through Beth’s freshman year of high school, weekends focused on recovery. Maybe a movie with friends or an excursion to the YMCA pool. Our packed weekdays were overwhelming and exhausting between school, physical therapy, occupational therapy, extensive homework, and frequent medical appointments. Every small action of life was a challenge. The approaching holiday season lost its appeal for me. Timber shrieked when I pushed his cage in a corner to make room for our artificial green tree. With everyone busy, I decorated most of the tree, topping it with a red glass cardinal. The sweet ornaments my kids made when they were little did not evoke the usual nostalgia. I fought more tears, thinking about my babies growing up and the end of childhood. I avoided people and neglected friendships. I dreaded the social interactions required at holiday choir concerts and other events; “How are you?” echoed from well-intentioned acquaintances. How should I respond? I would not share my regret in the high school lobby. I refused to be a lightning rod for pity. When I was asked about Beth, deadly health risks of quadriplegia came to mind. Instead, I said something about her amazing attitude and found an excuse to retreat. My counseling sessions slammed me every week with sharp dichotomies. I had no disability and fought with pain every day. I appeared calm and anticipated crisis. I loved my family and my heart ached. My guilt spilled over in waves. How could I contain it? My psychologist didn't know. She reminded me about all the things out of my control—which might have been helpful for someone in a better frame of mind.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) The summer after the car accident, my doctor increased the dose on my anti-depressant and gave me two referrals, one to a psychologist for counseling and another to a surgeon for my dislocated thumb. Overwhelmed with our new normal, I put the referrals on hold, but I set aside my qualms about taking medication. I needed to stay afloat. Starting high school pushed both of us to our limits. For Beth, it was the physical demands, and for me, it was working as a tutor with too little sleep. She actually liked school, in spite of tiring so easily. “Most of my classmates only knew me as the shy volleyball player that I was before my car accident, but everyone was welcoming and supportive.” On a cold fall morning, Beth had a low fever with congestion. Her small shallow cough reminded me of the weakness of her lungs. When I asked her to stay home, we argued, even though I didn’t want to make the call about missing another day of work. She insisted on going to school. When I transferred Beth from the car to her chair, I hit an ice patch and we slipped to the pavement. Maria helped me lift her sister into the wheelchair, but my rocky composure had tipped over a sharp edge. Though I did my best to hide escaping tears, a few noticed. I said my head ached, no big deal. I didn’t lie. If pressed, I gave assurances that it would let up soon. After school, I moved a wheezing Beth into bed and rushed to give her medicine and water before she fell asleep. She made a request, a frequent one, to not let her sleep too long; a stack of homework waited. Beth needed the rest more, but that was a battle I never won. Alone in the quiet as she slept, I couldn’t fight the heavy sadness anymore. Then, it disturbed me that I couldn’t settle myself down for what felt like a long time—but I kept trying. When John arrived home from work, I shared the immediate problem: whether or not I could get through another school day without losing control. And worse, whether or not I could calm myself down when I did. More than anything else, I had to function day to day for Beth. She depended on me and I would not let anything get in the way. John knew about my chronic headache, but I had worked hard to minimize and mask the guilt and depression. I didn’t want to worry him. I love many things about my husband, including his ability to be a good listener. He hugged me and asked me to quit my job at the high school and start counseling. I agreed with relief. He suggested going out to a restaurant. No, thank you. He offered to schedule a massage for me. No, thanks. While I called to set up my first session with the psychologist, John made dinner. We thought that counseling would help. |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed