|

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

Beth’s excitement grew with speaking engagements in Toledo and Tiffin plus interviews for two newspapers. She started a Road to Athens journal with her top three goals for the Greece Paralympics. “First, swim my best and feel good about races. Second, swim in finals one night. Third, have fun with the U.S. team.” The newspaper articles about Beth focused on inspiration, a label she disliked. In her mind, she lived her life the only way she could. In my mind, the word “inspiration” meant different things, some good and some not-so-good. At its best, inspiration motivates in positive ways. At its worst, it insults and exploits. What label would reporters choose if more people with disabilities had a fighting chance, with better support, education, and opportunities? With the Paralympics approaching in September, school schedules would keep the rest of my family home. I researched expensive overseas flights to Greece, as well as hotels. The last hectic month of high school barreled by. For prom, Beth wore a blue chiffon dress that fell below her knees. She sat in her wheelchair with the ends of long ribbons tucked under to avoid a tangle in the wheels. Maria styled her sister’s hair into a fancy "do" with small, shiny barrettes. Beth, Ellen, and Lizzy pretended to be ultra-serious models as they posed for silly pictures before the dance. High school ended in an anti-climactic way, with more important things ahead. At graduation, Beth wheeled up a ramp to the stage at the stadium and spoke to the crowd as one of four valedictorians in the class of 226 students. Ellen, also a valedictorian, gave a speech about how others change our lives. It reminded me of Beth and the song For Good, my favorite from the musical Wicked. On a whim, I bought tickets to see Wicked on Broadway later in the summer with my girls, and planned a road trip to New York City. None of us had ever been to The Big Apple. Another first—one that would establish a new favorite destination. Next: Graduation Celebrations!

0 Comments

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

Our family calendar looked like a work of art with many notes in different colors. Beth’s last few months of high school filled up with senior events. She kept up with swim training and National Team paperwork. Her scholarship applications paid off with presentations in three cities. Sadly, we would have to miss the spring wheelchair games in Michigan and Ohio. Beth trained a junior to take over the school newspaper and prepared the final issues. She studied for AP exams, though Harvard gave no college credits for AP scores. We shopped for a prom dress. She picked out a strapless style in light blue chiffon that fell between her knees and ankles—so it wouldn’t get caught in the small front wheels. Online, I showed her what looked like the perfect jeans, made especially for wheelchair users with a higher back and a lower front. She wasn’t interested. Predictably. Ready to be done with high school, Beth had a classic case of senioritis. My job as a group home manager taxed my time, always on my mind. Some aspects of the job seemed easier with repetition, like complicated medications. The overwhelming responsibility never changed. I anticipated problems, but many could not be diffused. I barreled through my twenty-four shifts with a nagging headache I did my best to ignore. On my days off, I fielded numerous phone calls from my staff. With the group home basement and every closet jammed full of stuff, I received permission to have a garage sale. I cleared out more than a few mice nests along with tons of junk. The residents helped enthusiastically to earn their own personal money for the possessions they chose to get rid of. A big success, the sale fell on a beautiful spring day. With the income from the home’s extra stuff, I planned a very rare vacation for the residents. The trip to Niagara Falls with two of my staff wouldn’t have been possible without the sale. The April day when I found another nest of baby mice at the group home, I gladly gave the agency my three-month notice and started the countdown to our Harvard adventure. Next: Minneapolis Trials! (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

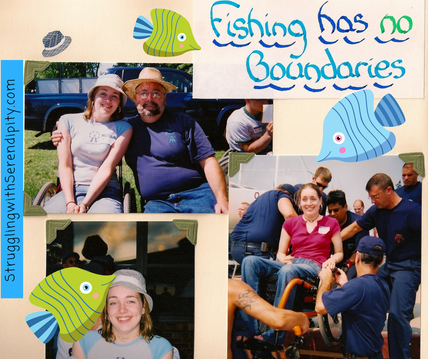

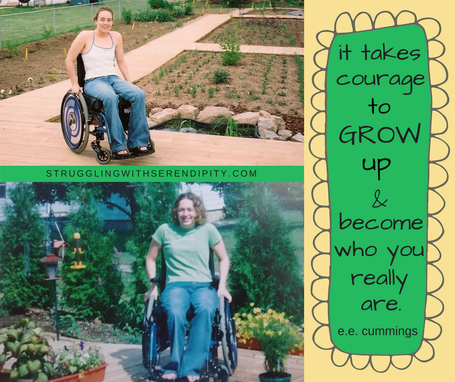

Beth felt ready to race with her high school team at the Sectional Championships. She swam the 50 freestyle in a fast 1:13.40, a short-course American Record in her S3 classification. Or, it would have been, except the officials messed up and the meet was not sanctioned, despite Coach Peggy’s advance request. The fastest swimmers at Sectionals advanced to the District Championships the following weekend. Someone with a physical disability like Beth had no chance of qualifying for the District meet. She planned to go to cheer on her teammates, but Peggy told her to bring her swimsuit and goggles. Since the District meet definitely would be sanctioned, the rest of Beth’s high school team unanimously voted to give her one of their relay slots so she could set her first two short-course American Records. The girls on the relay team gave up their chance to win because of the substitution. In the locker room, I helped Beth into her swimsuit while she stressed about their sacrifice. She also thought her high school season had ended the week before. It didn’t help when the meet announcer told everyone in the packed natatorium about her potential records before her relay started. Beth entered the pool from the side and swam to her lane. Meanwhile, Peggy moved into position, stomach down on the deck with her head over the water. Peggy reached low to grab Beth’s feet and hold them to the starting wall, a legal start for a swimmer with limited hand function. Repeated trials had determined the intricate details of Beth’s optimum position to start each stroke. An arm straight or bent, trunk angled or supine, and the mechanics of floating motionless until the starting buzzer. In the first leg of the 400 relay, Beth achieved her first two official short-course Paralympic S3 American Records, drawing enthusiastic applause from the large crowd. However, with the added stress, her time in the 50 free clocked in nine seconds slower than the week before, and the 100 free at seventeen seconds slower. Beth never asked for recognition, but hearing her new American Records announced at school on Monday morning was a nice surprise. Next: A Sudden Emergency!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Beth’s wheelchair didn’t rule out anything she really wanted to do. At 17, she started a dozen college scholarship applications and competed on the quiz bowl team. She continually volunteered with different groups, including the Tiffin student athletes who visited elementary schools. A Paralympic coach asked Beth to mentor a teenager from Seattle with a new spinal cord injury. The girls exchanged emails about wheelchairs and prom dresses. At the first practice of the season for the high school swim team, I sat on the YMCA bleachers with a book in case Beth needed me. I usually put on her swim cap—after she tried to do it by herself first—and lowered her from the wheelchair to the deck. Coach Peggy competently took over the tasks. Each swimmer carried a net bag with workout gear. In Beth’s, the typical flat paddles had been cut to a smaller size to fit her hands, with the flexible tubes adjusted to hold the paddles in place. Floating aids strapped on with Velcro. She also utilized a tempo trainer, a battery-operated device the size of a watch face. It worked like a metronome from music class, clicking out the ideal pace. I couldn’t imagine a better coach than Peggy. She modified the team’s workout with creative variations to avoid too much stress on specific arm and shoulder muscles. She also supervised circle turns. Beth couldn’t flip at the wall and push off with her feet like her teammates could. To finish a lap, she approached the wall at the left side of the lane, pushed off with one hand, and completed the half circle to start another lap. “Walls are bad for me,” Beth said. The fewer walls in a race, the faster her times. High school competitions took place in short-course, 25-yard pools. A 100-yard race required three circle turns at the walls. At the end of the first high school team practice, Beth swam to a corner of the pool. With her back to the corner, she placed her hands on the low deck to lift herself out of the water to a sitting position. She tried a few times, almost making it, before being lifted out. She always needed help to get from the deck to her wheelchair and didn’t mind when the boys on the team volunteered. I caught up with her on the way to the locker room, expecting to assist. Beth decided to go it alone for the first time and declined politely. She joined the rest of the girls in the locker room. I waited impatiently in the lobby, wondering if she changed her mind. Sitting in her wheelchair, Beth lifted a knee with her wrist to raise a foot. The opposite hand guided one side of her sweatpants over the dangling foot, before shifting to do the same for the other side. With the goal of placing her feet back on the chair rest with the pants bunched up around both ankles. Eventually, she used her fists and the one finger she could control to slowly pull the sweats up and over her knees. When the pants reached her thighs, she rocked from side to side to continue the prolonged fight. Next, she scooted forward and leaned her shoulders on the back of the chair. Anchored, she lifted her bottom up a few inches to pull the sweats all the way up—inch by inch. In the meantime, the rest of her team showered, changed, and left the YMCA, I found her in the locker room with the sweatpants mostly on. Beth’s first after-swimming solution for independence? Put on baggy sweatpants over a wet suit and then leave to shower at home. Easier said than done. Next: Travel Plans!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Managing the group home escalated my headache with less sleep and a full dance card. The base level of pain had gradually increased over a dozen years. How bad would it get? Over-the-counter medications didn’t make a dent. When I tried an opiate after surgery, I felt worse, not better. A prescription anti-inflammatory muted the headache—and increased my stroke risk. I read a study about how the brain gets wired to frequent pain signals, making it difficult to break the cycle. Obviously. I made a concerted effort to stay positive and suppress my fears of higher pain. At home, I kept up with Beth and drove her to swim practices on my evenings off. She took on new roles, unafraid, including the top job of news editor of the school newspaper, The Tiffinian. A feature in the paper titled Senior Superlatives reported on a class election that voted her most likely to be President and most likely to be rich. “I didn't want both so I gave the rich title away,” Beth said, with a laugh. The votes of her classmates also put her on the Homecoming Court, surprising her. “I was shy in high school,” Beth said. “I had more fun than most, but I wasn't a cool kid.” The night of the Homecoming football game, the Court arrived at the stadium in convertibles before lining up on the track to be presented to the crowd. A problem we didn’t anticipate handed Beth a rare defeat. “I wheeled myself everywhere, but my escort wanted to push my chair across the field,” she said, while also admitting the bumpy turf was difficult. It was a standoff on the 50-yard line, her escort equally as stubborn as Beth. She reluctantly gave in. “But I kept my hands on the wheels and pushed myself at the same time!” When the pageantry ended, Beth sat with her best friends on the platform in the student section to watch the game. Ellen and Lizzy gave her a bouquet of flowers and an adorable present. They made a Build-A-Bear and dressed it up with a fancy dress, homecoming crown, magic wand, and queen banner. They had been sure Beth would win. She didn’t, and hadn’t expected to. But... The queen bear was a sweet reminder of friends always in your corner.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Summer vacation wound down. At the YMCA, Coach Peggy tackled the difficult details of the freestyle. She moved in the water with the grace of a seasoned swimmer and often joined Beth in the pool to help with technique. Learning how to swim mimicked the physical therapy process. Beth paid close attention to detailed instructions and understood the goal. Small gains and slow progress did not discourage her. She visualized the future goal and put the pieces together bit by bit. Peggy asked Beth to join the Columbian High School swim team for her senior year. I had reservations initially. I knew the team had a great coach. I wondered if Beth’s participation would be mutually beneficial or a token inclusion? A reluctant Athletic Director also needed to be convinced, especially since accessible school buses were rarely available. As a compromise, I agreed to drive with my daughter to away meets. Watching Peggy at more practices, I trusted her instincts on the merits of the high school team. “Coach Ewald was excited to work with me from the first time I met her,” Beth said, “and she’s helped me make all my strokes better.” Soon after the Alberta swim meet, Beth, 17, made the U.S. Paralympic National Swim Team, a milestone achieved much earlier than expected. We celebrated with Maria and John over frozen yogurt sundaes. Beth called Ben first with the news since he followed her progress and understood the complexities of her S3 classification. National Team status included team swimsuits and other gear, as well as stipends for training costs and specific meets. And a big stack of paperwork. Beth’s lung doctors signed a long form to allow her only asthma medication, a maintenance drug. She needed to submit training logs year round. Each practice became an official workout with a coach’s plan written in a swimming shorthand I never learned. Team status also required reports of her daily whereabouts to facilitate random drug testing through USADA, the same agency that tested Olympic athletes. In August, I dropped off Beth and her friend at a John Mayer concert in Columbus. I easily imagined them singing loudly to the invincible lyrics of No Such Thing. The girls wore hipster hats bought for the occasion. Beth donned the same canvas hat with gray stripes during the 'Fishing Without Boundaries' weekend. John and I held hands and watched our talented daughters belt out a song in harmony on the karaoke stage at the hotel. On the boat the next day, Beth caught more Lake Erie perch than her dad for the second year in a row. NEXT! Wrapping up a non-stop summer: Fifteen Notable Firsts!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) My schedule aligned with Beth's since she couldn’t drive places independently with her wheelchair. After she achieved what I thought was impossible and swam forward in the pool, I worried less about disappointments she might face. Her confidence grew, along with her ability to push herself. Before Beth's junior year of high school ended, I drove three seventeen- year- old girls to physics day at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio. The sprawling amusement park filled with teenagers on a weekday. Beth and her friends decided to try a few roller coasters. They skipped the long lines for the rides to take their places at the front, joking about the perks of disability. They worked on their physics assignment and bypassed the rides that didn’t have enough physical support for a teenager with quadriplegia. We watched the Iron Dragon coaster and deemed it safe. Legs would dangle, but with a relatively smooth ride. Metal bars held the body in place securely. However, the Iron Dragon had no elevator and several flights up. I dragged the wheelchair up, rolling it on the steps for stability, with Beth facing down. She wrapped her arms around the back to stay in place. Two friends each grabbed a metal rod by her legs for back-up. When we arrived at the top, lifting Beth into the tight seat of the ride was much harder than we expected, even with extra help. I suggested we stop and go back to the wheelchair, but she wanted to continue. The fast pace of the assembly line stopped and people stared. Disheartened, I stepped back out of the way as the girls zoomed off. I wondered if our risk assessment was accurate. In no time at all, the girls flew back to the starting point and stayed put in the cars for another round. Beth gave me the thumbs up so I didn’t worry as much the second time. I should have stressed more about the narrow steps going down that were packed with people. Down the flights was not easier since the stairs were narrow and crowded with people. At one point, we made the mistake of lifting the chair wheels high off the concrete to try to get around other people, making it more precarious with a tilted chair (and a tilted Beth). Crazy. We were lucky she didn't fall. After that, we unanimously agreed to avoid stairs altogether for the rest of the day. When the heat of the day kept rising, my daughter looked pale and didn’t refuse Tylenol to bring her fever down. The girls found cold drinks and air conditioning in a restaurant, followed by an arcade. Beth never allowed hot weather to stop her plans and adventures. Just ahead: a nonstop summer!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) The sunshine of a new spring, along with my once-a-week counseling sessions, kept my well of worry from overflowing. Nearly three years post-injury, Beth showed me that her life with quadriplegia could be so much more than I had imagined at first. My anxiety dropped from a scary level to something more manageable. Chronic head pain remained a challenge. My obsession with worst-case scenarios improved from hourly to only some days. Most teenagers felt invulnerable and didn't worry about risks. That group included my youngest, despite her disability. We lived a few blocks from the high school and Beth liked the idea of wheeling there instead of driving with me. My first thought: NO! How could it be safe for her to cross alleys and streets in a wheelchair? Beth wanted to try. On a weekend, I walked next to her on a trek to the high school. The first obstacle involved wheeling over driveway stones to get to the sidewalk in front of our house. Next, the old neighborhood had broken sidewalks and no curb cuts. We tried a narrow alley instead that had bumps and stones and potholes. And almost zero visibility for cars with bushes blocking the view. When we crossed Tiffin’s Washington Street in between parked cars, drivers approached fast. On the high school grounds, there was no way to avoid either a long incline at the front entrance or a harder slope into the parking lot towards the automatic doors. I continued to drive her to and from school. The Quiz Bowl team finished a winning season, undefeated in the league. Against my advice, again, Beth joined the high school spring musical, Hello Dolly. She wore a headset to manage the stage crew while Maria shined in the lead role. After a show, I conversed with friends in the lobby without making a quick excuse to leave. The girls stayed out late at cast parties that followed the show's success. John and I dropped our strict curfew rule after the car accident. A spinal cord injury had changed our perspective, with a new awareness of what really mattered. And what didn't. Beth wasn’t happy with her ACT score for college, so she studied practice books before taking the test again. Not my idea. The second ACT improved on her first composite score by a surprising four points; she credited her English teacher, Mrs. Kizer, for her high English score. Beth set goals on her own and I supported her unconditionally, but not for bragging rights. More than anything else, I needed her to be okay, to be really okay, as she claimed the night of the accident. Was it too much to wish the same for myself, for everyone I loved, and for the rest of the world? Flowers burst into bloom in John's big garden with the ramped walkways. I loved the sunshine. Keeping up with Beth kept me busy and distracted most days, especially when my headache settled at a lower baseline. Lots of comings and goings. School, after-school activities, volunteering, swim practices, and time with friends. Sometimes I drove while Beth, often tired, dozed in the passenger seat. Overbooking her time shifted from a frequent inclination to an ingrained habit. She didn’t want to miss out on anything. Next week: Beth’s first swim competition with the forward freestyle! (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

I worked at not being a pushy parent and continued to follow my 16-year-old daughter’s lead. If Beth asked to go to the YMCA pool to practice on her own, we went, but I never suggested it. I worried about her getting run down from pushing herself too hard. Everything took more time and effort with a spinal cord injury. After Beth figured out the balance needed to move on her stomach in the water, the butterfly seemed to be the most doable forward stroke. She took a breath after two arm strokes of the butterfly, as she did with the backstroke. Breathing was more of a challenge with her initial freestyle attempts, but the breaststroke was the hardest. “When I first swam the breaststroke, I went backwards,” Beth said. Once a week in Toledo, she tried to learn the butterfly, freestyle, and breaststroke. A coach sometimes worked with her in the water before her backstroke laps. At her practices without a coach at our local YMCA, she experimented with the forward strokes, despite impaired arms and no use of her legs. Beth competed with the butterfly for the first time at the Turkey Meet in Toledo on Thanksgiving weekend. She loved how it felt to fly (slowly) through the water. She also selected her events for the Ohio Senior Meet in March. With typical courage, she signed up for the 150 Individual Medley (IM) that included strokes she could hardly swim. A week before the March meet, a Toledo coach suggested dropping the IM. Beth talked him into keeping it. It wasn’t smooth or pretty, but she swam the butterfly and breaststroke (and backstroke) nine months after Seattle at the Senior Meet in Erlanger, Kentucky. I lifted her out of the pool while the packed crowd applauded. Beth and I hadn't known that our hometown had a swim club — until they attended the same Senior Meet with their coach, Peggy Ewald. We had only known about the high school's team. Peggy talked to Beth’s Toledo coaches and volunteered to help with some of her solo practices in Tiffin. We met Peggy at the YMCA pool about once a week as Beth pursued her quest to master all of the strokes. They took on the intricate details of moving and breathing in the water. “Coach Ewald was excited to work with me from the first time I met her,” Beth said. (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) After every swim practice, Beth leaned into a corner, put her hands up on the ledge, and raised her body up as far as she could — before being lifted out of the pool. A familiar dynamic: complete assistance very (very) slowly becoming partial assistance, with her clear expectation that it would be no assistance in the future. As a junior in high school, Beth managed to keep up with a full school day, swim practices, volunteering, and extensive homework. She typed lab reports and essays on a standard computer keyboard. The early version of DragonSpeak, voice recognition software, never was used. She didn’t use the typing aid I bought that strapped on her hand or the supports to rest her forearms on. Beth used three fingers to type. She always relied the most on her left index, the only finger she could move a few inches, to press down on the keyboard. The useful left index also worked her laptop’s built-in mouse, set to respond to a soft touch. The same finger also hit letter keys on the left side and center. The index and pointer on her right hand contracted in an arc and focused on the right side of the keyboard. To type with those two fingers, she had to move her right hand to place a fingertip on a specific key, since she couldn’t move those fingers. When a finger or hand spasmed, she used another and kept going. Her accuracy was amazing, but in high school, her typing (and handwriting) was significantly slower than her peers. Against my advice, she took the American College Test (ACT) with no accommodations. Beth stubbornly refused extra time for assignments and tests. Her application for a lift chair to use at the pool was approved. We met with senior students at the University of Toledo who took Beth’s measurements and discussed the design. The chair would have a standard seat with back support and a toggle switch powered by a motor with a rechargeable battery. Sitting on the seat, she would push or pull a toggle switch to lower or raise the seat. The finished project impressively accomplished the task. At the YMCA, Beth stayed in her manual chair while I pulled the lift chair to a spot on the deck close to the water. She adjusted the seat bottom of the lift to a position slightly lower than the seat of her manual chair before moving onto the lift by herself. She used the toggle switch to move the seat down to almost floor level. From there, she used her arms to scoot to the deck and into the water without assistance. Unfortunately, we could not store the chair at either pool. I could barely lift the heavy device to put it in and out of the car, so it found a home in our living room. Beth used the lift chair to get on and off the floor independently, sometimes stretching out to do her homework while a familiar movie played in the background. Austin Powers movies were comedy favorites. John made the girls laugh with lines from silly movies. Beth found humor in her disability that her friends and family shared. At school, a friend scolded her for not standing up during the Pledge of Allegiance. When Beth’s friends gathered at our house, I loved to listen to their easy laughter.

Next week: more swimming serendipity... |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed