|

For Beth's third season on the Harvard Women’s Swimming and Diving roster, she added new pump-up songs to her swim meet iPod mix, including “Stronger” by Kanye West. I smiled when she sang along to the chorus. Maybe challenges really did make us stronger? During team practices, she usually typically swam a mile over two hours. In October, a doctor tried to drain her inflamed right elbow. He found no fluid, just swollen tissue.

Coach Becca worked with Beth during one-on-one sessions at Blodgett as well as team practices. “I never heard her complain,” the coach said in The Harvard Crimson. John and I looked forward to all of the HWSD home meets her senior year, often sitting sat with Maria in the red seats. At a November meet, with Harvard dominating the point count, three of Beth’s teammates wore flippers in a relay with my daughter substituted as the fourth. Other swimmers clustered at the end of the lane to cheer her on. She cut a whopping 10 seconds off her previous short course American Record in the 50 back, set at a HWSD meet only a year before. An article in the NCAA Champion magazine described how Beth, “added another level of excitement to home crowds at Blodgett Pool, especially when records were at stake.” “No matter what team we raced against,” Beth told a reporter, “people always came up to me and congratulated me. It was kind of strange sometimes, but I guess it's great for them to see someone with a disability compete on a college varsity team.” At the last home meet, swimmers on the men’s team honored Beth and the other seven seniors on her team with bouquets of flowers. Afterward, John, Maria, Beth, and I ordered pad Thai and big bowls of vegetable noodle soup at a Vietnamese restaurant in Harvard Square. The following weekend, I drove Beth to Yale in Connecticut to compete at the last away meet of the season. She laughed and clapped when the freshman swimmers on her team danced on the pool deck and sang, “We're All in This Together,” from High School Musical. Beth finished her Harvard career with six Paralympic American Records set at Blodgett pool in the free, back, and butterfly. *More exciting book news! Book talks and signings soon in Washington DC, Ohio, and Boston bookstores! bit.ly/mybooktour Hope to see you! My new memoir, Struggling with Serendipity, is available everywhere books are sold. Signed copies are available here: bit.ly/memoiroffer.

4 Comments

I have exciting news to share: I signed a publishing contract for my memoir, Struggling with Serendipity, with a traditional publisher (not self-publishing)! I wanted my awesome blog followers to be among the first to know, before I post the news on Facebook and Twitter. Thanks so much for your support! The next segment in my story follows.

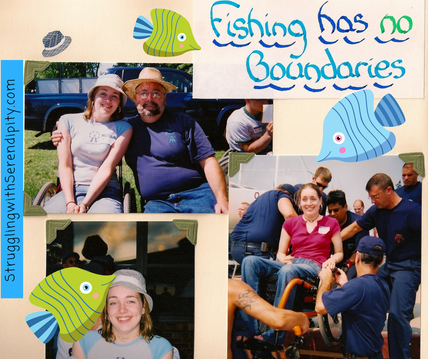

During John’s spring break, we drove twelve hours from Tiffin, Ohio to Cambridge, Massachusetts, taking Route 90 most of the way. It was worth it to spend a few days with Beth. A decade earlier, the one-hour drive from Tiffin to Vermilion seemed long, but no more. I bought tickets for our first Red Sox game at Fenway Park with John and Beth. The huge crowd at the stadium an hour before the game surprised me. We lined up by the field to meet some of the players. Many lingered to talk to the smiling college student in a wheelchair with the navy blue Red Sox cap. The stadium had old-fashioned charm. The homerun fence was painted bright green: the green monster. With every seat in the stadium taken, many others paid to stand to watch the game. The enthusiastic, rowdy crowd reacted to every play, something I’d never seen before. My first experience with intense Boston sports fans, but not my last. Bostonians are known for taking their professional sports teams seriously, a fact supported by many winning teams. We weren’t prepared for the cool weather, so I signed up for a credit card to get a free Red Sox blanket. I wrapped it around my daughter’s shoulders (and later cancelled the card). It was parent’s week at Harvard, so John and I visited Beth’s class on Ethics, Biotechnology, and the Future of Human Nature. Dr. James Watson, the former head of the Human Genome Project who discovered the structure of DNA with Dr. Francis Crick, was the guest speaker that day. His controversial affinity for eugenics created a lively discussion with the class. eugenics |yo͞oˈjeniks| the science of improving a human population by controlled breeding to increase the occurrence of desirable heritable characteristics. Developed largely by Francis Galton as a method of improving the human race, it fell into disfavor only after the perversion of its doctrines by the Nazis. Dr. Watson encouraged the Harvard students to have many children. Beth joined the class debate on the potential of stem cells and the controversy over discarded embryos for research. Though never focused on a cure for her disability, she supported medical research. An upcoming vote in Congress in the summer of 2006 heated up the debate across the country over federal funding for stem cell research. We didn't know that Beth would be in the middle of it. Next: A Life-Changing Experience!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Summer vacation wound down. At the YMCA, Coach Peggy tackled the difficult details of the freestyle. She moved in the water with the grace of a seasoned swimmer and often joined Beth in the pool to help with technique. Learning how to swim mimicked the physical therapy process. Beth paid close attention to detailed instructions and understood the goal. Small gains and slow progress did not discourage her. She visualized the future goal and put the pieces together bit by bit. Peggy asked Beth to join the Columbian High School swim team for her senior year. I had reservations initially. I knew the team had a great coach. I wondered if Beth’s participation would be mutually beneficial or a token inclusion? A reluctant Athletic Director also needed to be convinced, especially since accessible school buses were rarely available. As a compromise, I agreed to drive with my daughter to away meets. Watching Peggy at more practices, I trusted her instincts on the merits of the high school team. “Coach Ewald was excited to work with me from the first time I met her,” Beth said, “and she’s helped me make all my strokes better.” Soon after the Alberta swim meet, Beth, 17, made the U.S. Paralympic National Swim Team, a milestone achieved much earlier than expected. We celebrated with Maria and John over frozen yogurt sundaes. Beth called Ben first with the news since he followed her progress and understood the complexities of her S3 classification. National Team status included team swimsuits and other gear, as well as stipends for training costs and specific meets. And a big stack of paperwork. Beth’s lung doctors signed a long form to allow her only asthma medication, a maintenance drug. She needed to submit training logs year round. Each practice became an official workout with a coach’s plan written in a swimming shorthand I never learned. Team status also required reports of her daily whereabouts to facilitate random drug testing through USADA, the same agency that tested Olympic athletes. In August, I dropped off Beth and her friend at a John Mayer concert in Columbus. I easily imagined them singing loudly to the invincible lyrics of No Such Thing. The girls wore hipster hats bought for the occasion. Beth donned the same canvas hat with gray stripes during the 'Fishing Without Boundaries' weekend. John and I held hands and watched our talented daughters belt out a song in harmony on the karaoke stage at the hotel. On the boat the next day, Beth caught more Lake Erie perch than her dad for the second year in a row. NEXT! Wrapping up a non-stop summer: Fifteen Notable Firsts!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) At the Edmonton, Alberta swim meet, Beth met the other S3 women from Germany, Norway, Denmark, and Mexico. The women from Mexico and Germany held the top spots in the World Rankings; to race, they left their wheelchairs behind to stand and walk a step or two to the starting blocks. Their coaches helped them climb on and prepare to dive in. My daughter started the race in the water with an ineffectual push off the wall. With the tough competition, Beth didn’t expect to earn a medal for a top three finish. Also unexpected: the swimmer in the next lane stayed in her field of vision, sparking momentum. For the very first time in her life, she experienced how it felt to see and to race a true competitor, to beat her to the finish by less than a second, and to earn a third place international medal. Beth surprised us next with second place in the 100-meter freestyle race. Right after, officials tagged her for her first drug testing. They worked for the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), the same agency that tested Olympic athletes. Officials stayed close by as a Team USA coach supervised her cool down laps in a separate small pool. From there, Beth participated in her first ceremony for an international medal. Next, the coach explained the test procedure and walked with her while USADA officials led the way off the deck. In the 100- and 200-meter events, Beth finished ahead of the S3 women from Germany and Mexico. She started to think of herself as a distance swimmer. The five S3 women in Alberta, Beth included, swam slower than their previous best times. Small health issues like spasms, skin scrapes, minor infections, and low-grade fevers had a bigger effect on those with severe disabilities compared to others who did not. Temperature changes impacted quads in a negative way, as well as not drinking enough water. The physical stress of traveling and time changes also factored in, one of the reasons that teams going to the Paralympics every four years arrived in the area weeks ahead of the actual event. Beth rested in between the sessions of the three-day meet. No sight-seeing in Edmonton, except for the hilly view from the airport. From the stands, I watched Beth on the deck. In between races, she laughed at the antics of the teenage boys on the team. They “borrowed” the Australian team's frog mascot and noisemakers, stoking a friendly rivalry. During her medal presentations, I used my deck pass to take pictures. Beth earned her first international medals, two silver and two bronze. Medals that mattered. We landed in Detroit to discover the airline had lost a sideguard, one of two small curved plastic shields to protect clothes from wheelchair wheels. A new shield cost $100. I bought one and started the long process to be reimbursed from the airline. After Alberta, she took the sideguards off before she boarded a plane. Next destination of a non-stop summer: John Mayer in Columbus!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Hundreds of participants converged from all over the country for the Junior National Championships in Connecticut. Like Beth, many teenagers lived in places where they were the only ones with a visible disability in their class or school. At registration, we recognized a few teenagers from the Paralympic meet in Minneapolis two weeks before, and another from the Ohio Wheelchair Games. None of Beth’s friends from the Raptors had been able to join us. The first day, we found the large field house with many ping-pong tables set up and ready to go. Beth experimented and found a better way to use the tenodesis grip to angle the paddle by tilting her left wrist more. She decided to test how far she could lean to reach the ball without tumbling down, so at her request, I reluctantly removed the two armrests on her wheelchair. Beth surprised both of us by winning several games without falling to the floor. The armrests never went back on her chair. After the table tennis competition, caterers served a simple meal for the athletes and parents in attendance. Young servers stood behind the buffet table and wore clear plastic gloves to set out food. As we ate, a frustrated mom confronted the workers about the latex gloves they wore. Her son had a latex allergy, more common among kids with disabilities than the general population. (Thankfully, Beth never had a problem with latex.) I agreed with the mom about the need to use latex-free gloves at a disability event. Though I also felt sorry for the teenaged servers who were not personally responsible. At the swim competition, wheelchairs surrounded the pool. When Beth raced, I walked alongside on the deck. In her sights, I pretended to be a coach by waving my arms, the signal to kick harder. She set several new wheelchair sports records for her gender, classification, and age group. Not the coveted Paralympic American Records. Next destination of a non-stop summer: Mystic, Connecticut!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Beth led us to unexpected places after her spinal cord injury. “I always knew I was just going to get stronger and get back to my life as soon as possible,” she said. On May 10th, Beth drove us in her little blue car to the Michigan Wheelchair Games. Three years had passed since her injury and one year since her first swim meet in the same 25-yard pool. She competed using the forward freestyle stroke for the first time. Not a smooth endeavor and quite a bit slower than her backstroke. She dropped 30 seconds off of her 50 back race compared to her time one year before. I drove home from Michigan so Beth could rest. But first, she sang and danced in the passenger seat to her favorite John Mayer song. “I am invincible, as long as I’m alive!” Déjà vu. I loved our road trips. One week later, we attended the Ohio Wheelchair Games. Two weeks after that, Beth competed in Bowling Green at her first outdoor meet. She accepted my help to wheel over the grass to GTAC’s team camp. Her friend on the team was not in sight, so she picked a spot out of the way. She liked being outside and rarely complained about the heat. Hot weather raised her body temperature and I monitored it with a forehead gauge. She claimed to sweat a little, but I never saw it. Beth alternated her arms for the 100-meter backstroke instead of the double-arm technique, while the other swimmers in her heat swam a 200-meter event so she wouldn’t have to finish the race alone. Her swim times varied more from meet to meet than they did for her able-bodied teammates. She unexpectedly swam her fastest times by far in the 50-meter traditional forward freestyle race. She touched the wall at one minute and 28 seconds, still 15 long seconds away from the most difficult American Record in her S3 classification. I suspected that the swim parents with stopwatches fudged (improved) her time a little. Maria graduated from high school with honors in late May. We hosted a big graduation party on our backyard deck with John’s flowers and walkways providing a colorful backdrop. Maria chose to attend Tiffin’s Heidelberg College to major in education and take advantage of their acclaimed music program. She had intended to be a teacher ever since she toddled into her dad’s classroom. Since her sister’s injury, she decided to teach young children with a disability. She would be a passionate advocate for her future students. Always on the go, Maria babysat often, worked at a video store, took voice lessons, and performed in community theater. I loved her energy and enthusiasm. We all lived in the same house, but some evenings I didn’t see her. We met at Taco Bell sometimes to catch up over burritos and fountain drinks. Meanwhile, Beth made big plans for a summer to remember. (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

The logistics of swimming with quadriplegia evolved. Beth wore her one-piece suit to the Toledo or YMCA pool, but partway, up to her waist, with loose sweatpants over the suit and a T-shirt on top. In the locker room, I took off the shirt and pulled up the suit to put the straps in place. After a practice, I helped with the sweatpants over the wet suit before we headed home to shower. With improved, but not normal, balance, she asked to try the white plastic bench again. It worked with my help and we happily gave away the cumbersome metal shower chair with the rails. Five months after our Seattle trip, Beth achieved what I thought would be impossible. I watched at the YMCA pool as she advanced forward on her stomach for the entire 25-yard length for the first time, her arms working wildly below the surface but advancing at a snail’s pace. Her legs dragged behind. She conquered the basic balance of forward motion—without approximating a swim stroke. I expected her to stop at the wall after the 25 yards. Instead, she took only a moment to take a bigger breath before pushing off with her arms and going a little farther. Back on the wall to rest, she flashed a happy smile my way. Priceless. I returned her smile. All of my worrying and waiting for her optimism to plunge into depression had been wasted. Thankfully. For Beth, the achievement was only a small step toward a bigger goal. At the swim practices that followed, she worked on increasing the forward distance. And tried to add the arm movements of the butterfly, which seemed more doable at first than the breaststroke and freestyle. Her attempts to circle her arms out of the water while moving forward resembled a clumsy, erratic butterfly. Her backstroke had started in a similar way before finding a regular rhythm. I admired her tenacity, but I wasn’t sold on her mission to get better and swim all the strokes. No one knew how far she could go. I expected an impassable physical barrier to abruptly halt her progress. Not Beth. Legs and hands that didn’t work were a given. She accepted that her damaged arm and trunk muscles would not strengthen nearly as easily or nearly as much as perfect ones. Willing to wait weeks and months for small bits of progress, Beth tapped into a well of stubborn teenage persistence.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) When I drove to the Seattle pool for the second day, we loved how Mount Rainier seemed to float in a pillow of clouds on the eastern horizon. At the meet, a friendly official introduced herself and two others from her Toledo club team. They extended a warm invitation to join their team. We also heard about the next Paralympics in Greece, held shortly after the summer Olympics in the same venues. “I was hooked," Beth said. "I knew it wasn’t going to be my last national meet." I borrowed a page from Laraine’s book and took on the role of a foil, reflecting and questioning, not encouraging or discouraging. Should we pause and contact a Tiffin swim coach instead of driving an hour each way to swim in Toledo? Were swim coaches like medical specialists in the sense that they tended to be better in big cities compared to small towns? We had no clue. I worried about Beth taking on too much, especially learning new strokes, which seemed like an exercise in futility. Wouldn’t life be easier (better?) if she settled for a leisurely backstroke? Waiting for a race, Beth adjusted her ear buds and turned up her music. One 50-meter length with no turn felt less intimidating, but her time did not qualify for finals, again. That afternoon, we saw Seattle in a different way from a boat in the harbor. We treated ourselves to a fancy ice cream dessert with chocolate shavings and extra whipped cream, the first connection of ice cream to swim meets. The third morning, we tried to sort out a jumble of criteria on the papers posted on the walls of the pool. Unreasonably fast times to make the U.S. National Team. Ludicrous times for World Records—only slightly less ludicrous for American Records. All broken down into strokes, distances, classifications, and genders. For almost every American Record for S3 women, there were blank lines where a name should be, along with a fast, arbitrary time that no one had achieved before. The last evening of the meet, we watched the finals races. Beth also officially enlisted the help of the Toledo coach to find out what she could do in the water. She told him that one year ahead, at the next national championship, her swim times would be fast enough to qualify as an S3 and make the cut for finals. Not stopping there, she also planned to swim all the strokes. Beth had the gift of perpetually underestimating challenges. The World Rankings of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) compared individual swimmers. Beth’s three very slow races in Seattle placed her on the list at 15th, 17th, and 21st in the world, confirming the rarity of S3 swimmers. I arrived back home in Ohio with a missing push handle on the wheelchair, Maria’s unbroken Snow White mirror, and a 16 year old intent on learning how to swim. Occasionally floating across the pool had been a pleasant pastime before Seattle. After the national meet, Beth raised the bar to the sky for her first swimming summer. (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

The Seattle meet officially opened with the beeps and buzzes of back-to-back events. Most swimmers dove off the blocks from a standing or sitting position with no assistance. Those with impaired hands usually started races in the water. One coach reached over the edge to hold a swimmer’s feet to the wall. Another coach held an arm before the buzzer sounded. A man with no arms floated on his back, with his feet touching the wall and a cord in his teeth. The coach at the other end of the taut cord dropped it at the start. The only people we recognized had been at the Michigan Games: Shawn and his wife, as well as another teenager and her mom. There were a few more wheelchairs in use compared to the night before; a girl minus a prosthetic leg pushed a manual wheelchair with strong arms, instead of using crutches on the wet deck. We clapped for the first American Record of the meet, a neck and neck race. It quickly became evident that I had misunderstood Shawn from the start. Beth had no innate swimming talent. His invitation had been based on the fact that a tiny percentage of quads around the world could be alone in a pool without drowning. Even more rare: quads who could swim. Beth had the dubious honor of being the only S3 female from the United States at the meet, a distinction that would reoccur again and again. The fastest athletes during prelims would return to race in the early evening, if they beat the cut times for the finals races. The humidity of the chlorine air saturated my skin, but Beth couldn’t sweat if she wanted to because of her spinal cord injury. I rushed back and forth to the concession stand for cold drinks. For Beth’s first race at her first nationals, swimmers on both sides entered the water without a mother’s help and surged ahead at the start. My daughter merely sought to prevail over the seemingly endless distance of the 50-meter pool—twice. The only one weaving down the lane in the last stretch, she did not make the cut for finals, as expected. In the women’s locker room, swimmers showered and changed on their own. Beth chose an out of the way spot by the back lockers because she needed my help. Our hotel had no accessible rooms available, so instead of being lifted in and out of a bathtub, she decided to shower at the pool in her wheelchair for the first time. I took off the cushion ahead of time, adjusted the tight water handle, and picked up the soap when it slipped from her lap. I squeezed out the shampoo and her arms trembled slightly as she moved it around in her hair. The wheelchair left drips of water on the concrete on the way to the rental car. After a quick lunch and a nap at the hotel, it was time to explore. I had a stack of printed Google map directions that Beth read while I drove to the fisherman’s wharf and the Space Needle. After riding the elevator to see the panoramic vista, we found an unusual store. I bought Maria a small but elaborate Snow White mirror for her upcoming birthday, hoping I could get it home in one piece. My girls would always be Snow White and Cinderella, princesses who believed in happy endings. At five, Maria decreed that we would live together forever in our Tiffin home, in our tiny corner of a big world. “The trip was truly amazing,” Beth said. “Seattle was beautiful. My mom and I were able to tour the city in the afternoons and evenings after I swam.” We didn’t know that the Seattle swim meet would be the first and the only one where she would not qualify for finals.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Parallel to the Olympics, U.S. Paralympics supports athletes with impairments. Classification compares the absence of function between those with limb differences, spinal cord injuries, spina bifida, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and more. To complicate matters, individuals with the same diagnosis often have different motor abilities. The specific criteria to classify a swimmer usually leaves little room for debate or error—except for the most severe physical disabilities (S1 to S4), catchall categories with less precise guidelines. On the wide deck of the nearly empty pool in Seattle, classifiers asked Beth questions. Her sincere answers minimized her quadriplegia. I thought about interrupting, but with muscle testing next, they would get a more accurate picture. For the last assessment, I lowered Beth from her chair to the pool deck. She positioned herself at the edge before falling into the water. Classifiers observed closely as she did her best to comply with their requests. When asked to swim the breaststroke, she kept her arms in front of her in a variation of treading water. Her head dipped underwater after a few seconds. Swimming forward on her stomach for the butterfly, freestyle, and breaststroke looked impossible. The classifiers openly debated between S2 and S3 before settling on S3. Beth looked down and paused before thanking them. If they had said S2, her unofficial classification from the wheelchair games, her swim times rocked. The same times would not qualify for the Seattle meet as an S3; however, newly classified swimmers could race regardless. It made sense that a novice who had never worked with a swim coach would need to improve before ranking among the best. After her appointment, Beth and I stayed at the pool complex for the picnic dinner to kick off the meet. We sat out of the way and watched the friendly crowd. Amazingly few athletes used a wheelchair. In street clothes, many had invisible disabilities. “There were about 200 athletes from eight different countries,” Beth said. “The entire Australian and Mexican National Teams were there.” We returned to the pool early the next morning for the first of the three day meet. A wide span of physical differences were apparent, but no one stared or judged. Paralympic rules banned artificial limbs and other supports in the water. Prosthetic legs propped casually on the bleachers underscored the unspoken acceptance of disability. Swimmers warmed up in the pool before the morning’s preliminary races (prelims) to the beat of pop music. An announcement informed us that those classified S1, S2, and S3 should use a specific end lane to warm up. No explanation was given because it was obvious: to avoid collisions with those who streaked down the right side of the lane, flipped to change direction, pushed off the wall with their feet, and swam back on the right side, completing a circle. Beth shared the designated lane with a few others for the first time and spent more time hanging on the wall than warming up. The other lanes teemed with fast, circling swimmers watched by attentive coaches. We only had each other, small fish in a big pond. |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed