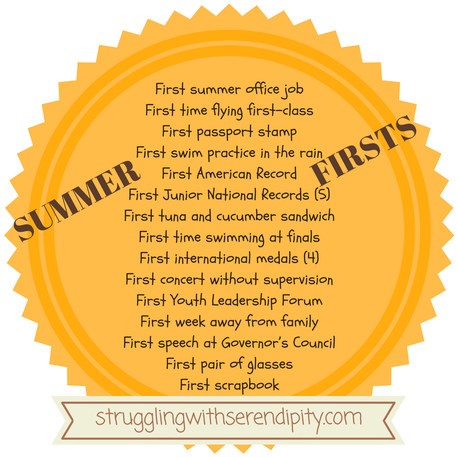

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) College applications covered our kitchen table before Beth’s senior year of high school began. She questioned the need for help at college her freshman year and wondered if I could live off-campus instead of in the dorm with her. Separate housing for me for any amount of time would add costs on top of her out-of-state tuition, room, and board. High college expenses seemed certain. John and I decided not to hold her back because of finances. We owned the Tiffin house and planned to borrow off it. My second counselor moved away and the third nudged me forward. After nearly three years of weekly sessions, I had few tears left. I had been spinning in a rut, perseverating on my choices the night of Beth’s injury. As if I had a replay option. The new psychologist told me the accident could not have happened any other way. She framed it as less of a colossal failure and more of a perfect storm of events. I woke up very early that morning to set up a refreshment stand for the choir contest. John stayed home to study for his National Board test. The night of the accident, the OSU concert ran longer than expected. The psychologist’s next point hit home: I could not make a good decision (i.e., calling John on the pay phone), because exhaustion impaired my judgment. That fact somehow flipped a switch for me and allowed a measure of forgiveness. However, no amount of reasoning would be enough, if Beth had been unhappy. I gradually reduced my zoloft to a lower dose. As always, my headache tightrope remained, a precarious and somewhat mysterious balancing act to keep the level manageable. At home, Beth gathered summer mementos and made colorful collages with a small paper cutter. She used markers to add descriptions and funny comments on each page, approximating the calligraphy style she learned before her injury. She created a tribute to the magical summer in her first scrapbook. The last page listed 15 notable summer firsts, including her first US Paralympics American Record, her first passport stamp, her first tuna fish and cucumber sandwich, her first concert without a parent, and her first swim practice in the rain. Beth’s very best ‘first’ of the summer: wheeling around Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

4 Comments

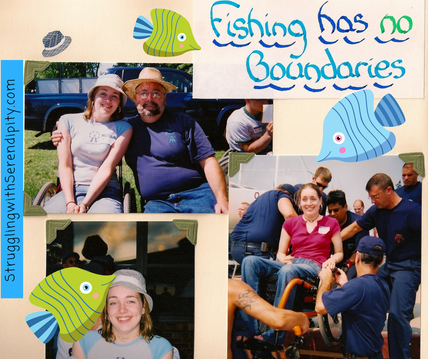

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Summer vacation wound down. At the YMCA, Coach Peggy tackled the difficult details of the freestyle. She moved in the water with the grace of a seasoned swimmer and often joined Beth in the pool to help with technique. Learning how to swim mimicked the physical therapy process. Beth paid close attention to detailed instructions and understood the goal. Small gains and slow progress did not discourage her. She visualized the future goal and put the pieces together bit by bit. Peggy asked Beth to join the Columbian High School swim team for her senior year. I had reservations initially. I knew the team had a great coach. I wondered if Beth’s participation would be mutually beneficial or a token inclusion? A reluctant Athletic Director also needed to be convinced, especially since accessible school buses were rarely available. As a compromise, I agreed to drive with my daughter to away meets. Watching Peggy at more practices, I trusted her instincts on the merits of the high school team. “Coach Ewald was excited to work with me from the first time I met her,” Beth said, “and she’s helped me make all my strokes better.” Soon after the Alberta swim meet, Beth, 17, made the U.S. Paralympic National Swim Team, a milestone achieved much earlier than expected. We celebrated with Maria and John over frozen yogurt sundaes. Beth called Ben first with the news since he followed her progress and understood the complexities of her S3 classification. National Team status included team swimsuits and other gear, as well as stipends for training costs and specific meets. And a big stack of paperwork. Beth’s lung doctors signed a long form to allow her only asthma medication, a maintenance drug. She needed to submit training logs year round. Each practice became an official workout with a coach’s plan written in a swimming shorthand I never learned. Team status also required reports of her daily whereabouts to facilitate random drug testing through USADA, the same agency that tested Olympic athletes. In August, I dropped off Beth and her friend at a John Mayer concert in Columbus. I easily imagined them singing loudly to the invincible lyrics of No Such Thing. The girls wore hipster hats bought for the occasion. Beth donned the same canvas hat with gray stripes during the 'Fishing Without Boundaries' weekend. John and I held hands and watched our talented daughters belt out a song in harmony on the karaoke stage at the hotel. On the boat the next day, Beth caught more Lake Erie perch than her dad for the second year in a row. NEXT! Wrapping up a non-stop summer: Fifteen Notable Firsts!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) At the Edmonton, Alberta swim meet, Beth met the other S3 women from Germany, Norway, Denmark, and Mexico. The women from Mexico and Germany held the top spots in the World Rankings; to race, they left their wheelchairs behind to stand and walk a step or two to the starting blocks. Their coaches helped them climb on and prepare to dive in. My daughter started the race in the water with an ineffectual push off the wall. With the tough competition, Beth didn’t expect to earn a medal for a top three finish. Also unexpected: the swimmer in the next lane stayed in her field of vision, sparking momentum. For the very first time in her life, she experienced how it felt to see and to race a true competitor, to beat her to the finish by less than a second, and to earn a third place international medal. Beth surprised us next with second place in the 100-meter freestyle race. Right after, officials tagged her for her first drug testing. They worked for the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), the same agency that tested Olympic athletes. Officials stayed close by as a Team USA coach supervised her cool down laps in a separate small pool. From there, Beth participated in her first ceremony for an international medal. Next, the coach explained the test procedure and walked with her while USADA officials led the way off the deck. In the 100- and 200-meter events, Beth finished ahead of the S3 women from Germany and Mexico. She started to think of herself as a distance swimmer. The five S3 women in Alberta, Beth included, swam slower than their previous best times. Small health issues like spasms, skin scrapes, minor infections, and low-grade fevers had a bigger effect on those with severe disabilities compared to others who did not. Temperature changes impacted quads in a negative way, as well as not drinking enough water. The physical stress of traveling and time changes also factored in, one of the reasons that teams going to the Paralympics every four years arrived in the area weeks ahead of the actual event. Beth rested in between the sessions of the three-day meet. No sight-seeing in Edmonton, except for the hilly view from the airport. From the stands, I watched Beth on the deck. In between races, she laughed at the antics of the teenage boys on the team. They “borrowed” the Australian team's frog mascot and noisemakers, stoking a friendly rivalry. During her medal presentations, I used my deck pass to take pictures. Beth earned her first international medals, two silver and two bronze. Medals that mattered. We landed in Detroit to discover the airline had lost a sideguard, one of two small curved plastic shields to protect clothes from wheelchair wheels. A new shield cost $100. I bought one and started the long process to be reimbursed from the airline. After Alberta, she took the sideguards off before she boarded a plane. Next destination of a non-stop summer: John Mayer in Columbus!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) An unexpected invitation led to an eight-hour flight. U.S. Paralympics Swimming invited Beth to attend the Canadian Open SWAD (Swimmers With A Disability) meet in August with the National Team. My daughter accepted before we looked up the location of Edmonton, Alberta. From Tiffin, the trip would cross almost 2,000 miles. We invited Peggy to join us. We packed Beth’s brand-new passport and her iPod, with a new playlist for meets. For her second flight since the accident, we kept her wheelchair until she boarded the plane. I helped her transfer to an aisle chair on the jet bridge, then grabbed her chair cushion and left the chair, tagged and gate-checked with strollers, to lower the probability of damage, at least a bit. I imagined the wheelchair on top of the luggage pile instead of under it. We traveled in style when an airline clerk upgraded our economy tickets to first class, our initiation to warm hand towels and extra soda. A welcome distraction for a long flight, with full meals instead of the snacks offered in the cheap seats. I helped Beth shift and raise her legs periodically through the eight hours in the air. When we landed in Alberta, Beth’s wheelchair had a bent wheel that made it harder to push. Traveling necessitated frequent repairs, especially replacing worn out wheel bearings. They wore out quickly after getting drenched often during locker room showers. The many countries at the meet created a festive atmosphere. Each team wore national colors and a country’s flag hung near the deck bleachers claimed by a specific country. The stars and stripes hung from the front of the high spectator seats where I watched with other U.S. fans. I understood that Beth didn’t want to be the only one sitting with her mom and wearing a Team USA shirt. Peggy assisted her on deck. I had a deck pass so I could help in the locker room. An unanticipated perk of the pass allowed me to take pictures on deck during medal presentations. Still somewhat shy, Beth made more of an effort to meet other teammates while I talked to other parents. They shared news of grants from the Challenged Athletes Foundation to help with the costs of competing. Also, three teenagers on the U.S. team had recently learned they shared the same birthplace in Russia. They had limb differences and had been adopted by U.S. families who lived in different parts of the country. I listened to stories, from cerebral palsy at birth to a young girl’s sudden-onset neuromuscular disorder. She walked home from school one day and collapsed on the floor. Life can change in a moment. Everyone has a story... Next: First International Medals! |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed