|

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) I stopped counseling since I was perfectly fine. After all, I finally made progress in the wake of three years of weekly sessions. Guilt and anxiety no longer dominated my days, which felt like a monumental gift. I scheduled dentist appointments to fix my second cracked molar, casualties of teeth clenching—despite the biteplate I wore each night. My doctor added a temporary muscle relaxant at bedtime to reduce the clenching. A high dose of Celebrex usually tempered the headache and kept me moving. I watched Beth hold a pen awkwardly in her right fist, not hesitating as she wrote her motto on a Challenged Athletes application. ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE. She wholeheartedly believed the motto was true. And it really was, though only for her and a small percentage of other people with her priceless perspective. Those with and without a disability. I filed away a note to myself that said, “Anything is possible, except when it’s not.” I intended to write about how she dismissed all she couldn’t do as irrelevant. “I think walking is over-rated,” Beth said, with a smile. Unable to stand and not focused on a far-off cure for quadriplegia, she continued to work hard to defy the usual limits of quad hands. Her spinal cord injury erased normal finger function. Even so, she wouldn’t write off any fine-motor tasks she really wanted to do. One example of many: putting her hair up in a ponytail after trying several times a day for two years. A tribute to unwavering belief and persistence. As Beth's last year of high school started, she quietly completed an early admission application to Harvard, convinced it was a long shot. “I didn’t tell anyone since I didn’t think I would get in,” she said. If someone asked about college plans, Beth mentioned the University of Michigan, one of the colleges she planned to apply to after she heard back from Harvard in December. NEXT: A new job!

6 Comments

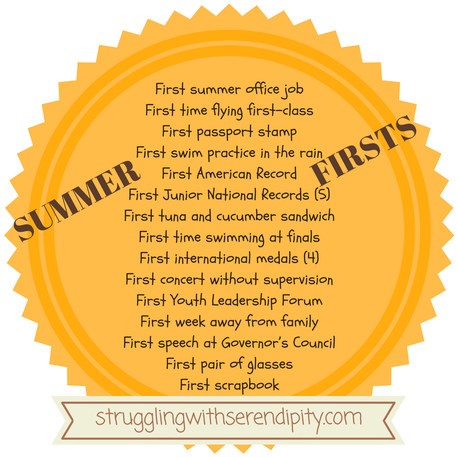

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) College applications covered our kitchen table before Beth’s senior year of high school began. She questioned the need for help at college her freshman year and wondered if I could live off-campus instead of in the dorm with her. Separate housing for me for any amount of time would add costs on top of her out-of-state tuition, room, and board. High college expenses seemed certain. John and I decided not to hold her back because of finances. We owned the Tiffin house and planned to borrow off it. My second counselor moved away and the third nudged me forward. After nearly three years of weekly sessions, I had few tears left. I had been spinning in a rut, perseverating on my choices the night of Beth’s injury. As if I had a replay option. The new psychologist told me the accident could not have happened any other way. She framed it as less of a colossal failure and more of a perfect storm of events. I woke up very early that morning to set up a refreshment stand for the choir contest. John stayed home to study for his National Board test. The night of the accident, the OSU concert ran longer than expected. The psychologist’s next point hit home: I could not make a good decision (i.e., calling John on the pay phone), because exhaustion impaired my judgment. That fact somehow flipped a switch for me and allowed a measure of forgiveness. However, no amount of reasoning would be enough, if Beth had been unhappy. I gradually reduced my zoloft to a lower dose. As always, my headache tightrope remained, a precarious and somewhat mysterious balancing act to keep the level manageable. At home, Beth gathered summer mementos and made colorful collages with a small paper cutter. She used markers to add descriptions and funny comments on each page, approximating the calligraphy style she learned before her injury. She created a tribute to the magical summer in her first scrapbook. The last page listed 15 notable summer firsts, including her first US Paralympics American Record, her first passport stamp, her first tuna fish and cucumber sandwich, her first concert without a parent, and her first swim practice in the rain. Beth’s very best ‘first’ of the summer: wheeling around Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Two and a half years after Beth’s spinal cord injury, I expected a gradual catharsis with my weekly counseling. But sessions still only stirred up tearful regrets for causing the accident. I thought that I must be doing something wrong, that I failed at therapy. After, I sat in the car, breathing deeply, until I carried no visible baggage home. I scheduled more appointments, hoping to find the person I had been before the accident. I was determined to redeem myself with Beth, though others needed me, too. And I needed them. I was intensely grateful for the people in my life. I wished gratitude could cure anxiety. Trying to look normal was a challenge on days when worst case scenarios dominated my thoughts. I had to concentrate to pay attention, even with my immediate family, though there was no lack of love or genuine interest. Unlike Beth, I had no grand goals. What I basically wanted — after magically erasing Beth’s injury — was the absence of pain. No headache that ebbed and flowed. No guilt and depression. No anxiety that also ebbed and flowed. Some days, Beth emanated vulnerability, a lifelong quad perpetually haunted by scary health risks: autonomic dysreflexia, serious infections, bladder stones, blood clots, and pressure sores. On other days, she looked to me like the happy and healthy teenager that she actually was. As a high school junior, Beth never saw the need to say no to extra activities. On top of AP classes and too much homework, she volunteered for fundraisers with the Raptors and for community events with the National Honor Society. She wrote for the school newspaper and worked on the yearbook. She followed her brother’s lead and earned a spot on the Quiz Bowl team. Her specialty: literature. A doctor also asked her to exchange emails with another teenager with a new spinal cord injury. Beth needed me less often, but I was there when she did. At the YMCA pool, on her forward motion quest, she progressed to spending more time with her head above water than under it. I read a book again while I sat on the bleachers, instead of watching every minute. One evening, she finished a backstroke lap as her high school’s swim team arrived to practice. As a few friends stopped to say hello to her, their head coach, Peggy Ewald, introduced herself to Beth... A fortunate accident. Serendipity.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Beth’s second year of high school would hold different challenges than the first. When she started her sophomore year, sixteen months after her injury, I could get through the days without crying in front of anyone, a victory of sorts. “My small group of really close friends in high school helped me in many ways,” Beth said, “including breaking my leg spasms and carrying my book bag. By the second year I had those things under control, but a friend continued to sit by me in class only because it was more fun that way.” I took a short cut through the school cafeteria on September 11th at lunchtime and paused by a strange crowd of silent students in front of the television screen. It took only a moment to get my first glimpse of unthinkable tragedy. I rushed to the locker room, relieved to find Beth and Maria waiting for me. Hugged close and safe, for the moment. I grieved with the nation, overwhelmed by the scale of the losses and the faces of children who would never grow up. My worst-case scenarios amplified after 9/11. Terrorism took on a life of its own in my mind, growing and mutating into an on-going and imminent threat. I tried to tap down the fear by storing bottled water in the basement and packing an emergency duffle bag. I wrote phone numbers and a meeting place on a small rectangle of paper, copied and laminated for each member of my immediate family to carry in their wallet. An article that I read caused me more worry, about the terrible knowledge that nuclear weapons had already been used in the past, and might be used again. My heightened fears grouped nuclear weapons with terrorism and a deadly virus. Toxic chemical spills were a high risk in Ohio with the heavy truck traffic. And a personal, selfish anxiety about any number of alarming events that could restrict prescription drugs; I was acutely aware of my addictions with antidepressants and pain medicine (not opiods, thankfully). Who would I be without the prescriptions? How would I help Beth? The very worst part of my anxiety was feeling helpless—powerless, useless—to protect my family. My counseling sessions after 9/11 were more emotional. My psychologist patiently explained to me that widespread catastrophe would be highly unlikely, as though that would comfort me. The tragedy of 9/11 had been unlikely. Our car accident and Beth's injury had been unlikely, too. I really (really) wanted to be optimistic, and picked up books at the library with positive messages. I wished that getting rid of anxiety could be as simple as just choosing not to worry. Just choosing to have hope. When Beth asked to go to the YMCA a few times a month, I read books on the pool deck while she moved on her back with her arms waving slowly underwater. I no longer needed to watch continually for her head dipping too long under the water. When I drove to Green Springs after school for physical therapy, Laraine encouraged her to keep swimming. Though technically, she was floating. I joined Beth in the water one Sunday at her request. She wanted to try the backstroke. The effort to rotate her arms out of the water caused her to sink. I splashed my face to hide my tears as I lifted her up. We had no way of knowing that the backstroke would be her fastest swim stroke.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) I convinced Beth to take a day off of school to go to the Shriners Hospital. Two volunteer drivers met us in Toledo early in the morning. We left our car there and boarded their van for the four-hour drive to Chicago. The friendly drivers lived in our hometown, Tiffin, and one was the grandfather of a friend. The Shriners Hospital made a colorful first impression, effectively designed to be welcoming for families. Beth and I met individually with each member of a large team at the spinal cord injury clinic, including a urologist, orthopedic surgeon, social worker, occupational therapist, psychologist, and physical therapist. A bubbly nurse took us on a tour of the hospital, pointing out a display for the Make-A-Wish Foundation for children with life-threatening medical conditions. She casually offered to make a referral for Beth, and introduced us to another quad and her mom who recently returned from a cruise in Alaska through Make-A-Wish. My family had rarely traveled. However, the offer bothered Beth. Between appointments, we talked. Make-A-Wish clashed with her wholehearted belief that her “condition” would get better, not worse, based on the one scale that mattered to her—decreasing dependence. She knew that cut spinal cords did not get better, and the medical miracle of re-growing cut cords might not happen in her lifetime. The frightening severity of her recent pneumonia and other risks of quadriplegia did not factor into her decision. Beth turned down the nurse’s offer, certain that others needed Make-A-Wish more than she did. I trusted my daughter’s judgment over my own. The entire team at the Shriners clinic convened with us at the end of the day to make recommendations. We learned that Beth’s damaged back muscles changed the spinal column and worsened curvatures. She acquired two new diagnoses. I had never heard of kyphosis, an outward bowing of the back, but I understood scoliosis, a curvature sometimes resembling the letter S. When I was a teenager, way back when, I had worn the Milwaukee back brace, an antiquated treatment for scoliosis. The brace covered my pelvis, with a metal bar that curved out in the front and connected to a chinrest, making three years of junior high and high school more awkward for me than usual. If the curving and bowing of Beth’s back continued to worsen, her organs could be damaged and major surgery would be needed to straighten the spine with a metal rod. I added back surgery to my ocean of anxiety. I worried for Beth, for the rest of our family, for friends, and for the whole world. The relentless ache in my head dug in deeper, filling the space behind my eyes. I talked to my psychologist every week about pain, guilt, and depression. She told me that guilt could resemble grief and offered rare advice: find things to look forward to. In other words, stop waiting for the next tragedy or health crisis. Easier said than done.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Six months had passed since the accident. Beth’s glass cuts healed and left small scars. She approached her new normal hour-by-hour and day-by-day. Beth had no expectations and no destinations. I had definite expectations for my first counseling session. When I fell asleep at the wheel, my identity as a mom had shattered along with the bones in Beth’s neck. I thought that my psychologist would bestow a smidgen of peace, with more mending on the horizon. In reality, my first hour of counseling simply tore off the scab on my guilt. After the session, I sat in the car in the parking lot and sobbed, haunted by Beth’s fragility and my own. Tears offered no redemption. Afraid of every aspect of the future, I waited for her outlook to cloud and crash. And selfish thoughts: when it did, could I function? I hoped for help at my next counseling session, or the one after that. We found a community of support in an unlikely place. I encouraged Beth to go with me to Toledo on a school night. When we entered MCO rehab, the look we shared spoke volumes; we were glad that she had moved to Green Springs for rehab instead of MCO. In the therapy room, we met the awesome members of the Northwest Ohio Chapter of the National Spinal Cord Injury Association (NWONSCIA) for the first time. Family centered, the large group included all ages and abilities, as well as several Laraine alumni. Deb O., our friendly favorite, extended a warm welcome and introduced Beth to the other teenagers. Most had spina bifida from birth, making them wheelchair masters from an early age. We listened with interest about annual events, including a summer fishing trip and the wheelchair games. I also overheard a hushed conversation between two parents about a young man with quadriplegia who died on the way to the hospital from a stroke caused by autonomic dysreflexia. On our way home from Toledo in the dark, Beth watched the road nervously. A new anxiety surfaced with night driving, regardless of who was behind the wheel. Still, I felt the need to reassure. I told her that I must be the safest person to drive with; I knew what it felt like to be too tired and would never let that happen again. I offered again to find a psychologist for her to talk with, and she declined, again. Driving at night would continue to trigger anxiety. However, it would not prevent Beth from traveling where she wanted to go. |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed