|

My oldest daughter Maria stuck to her plan to relocate to Boston when she graduated from Heidelberg. She hustled with a heavy class load to finish a double major in three and a half years. Before long, two of our three children would be in Massachusetts.

John agreed with me that we could live there, too. He knew how much I wanted to be with our kids. He started his thirtieth year of teaching in Tiffin, his last before retiring in Ohio. We planned to sell our house in the spring and move that summer. John decided he’d teach for a few more years in the Boston area because of the much higher cost of living there. At Harvard, Beth swam six times a week her junior year, and rode the bus at 6 a.m. with her teammates who lived in the Quad. She often arrived at Blodgett in sweatpants, with a swimsuit underneath that she’d pulled on before getting out of bed. The team stretched together on deck before getting in the water. Skipping practice? Not an option. When the rest of the team swam doubles, a second practice on the same day, Beth stayed with one. Coaches added a snorkel to the modified swim paddles and floats in Beth’s equipment bag. The snorkel eliminated the breathing challenges of her forward strokes. During hour and a half workouts, she typically swam about a hundred laps of 25 yards each. During peak times in her training cycles, workouts hit two hours and 3,000 yards, almost two miles. “My undergrad was devoted to swimming and health policy,” Beth wrote. “It was a struggle sometimes to be independent and keep up with the work, but I grew a lot during that time. I learned how to make new friends, to manage my disability, and to advocate for myself—not to mention becoming a much stronger swimmer. I like to joke that I spend more time in the pool than I do in class. I love this pool!” The locker room had a new plastic shower chair Beth finally requested. From a sitting position in her wheelchair, taking off a wet swimsuit in the varsity locker room required patience. I suggested suits one size bigger, but she liked them tight. Resolve and repetition gradually made dressing in her wheelchair easier, from button down sweaters to the zipper on her skinny jeans. Next: My New Job!

6 Comments

Back at Harvard for the start of Beth’s junior year, I carried her chair and other items up from the basement storage room. I set up her dorm room before I drove back to Tiffin. She changed her concentration from biology to health care policy with the goal of attending law school. Beth told a reporter about her DC summer and why she changed her major.

“I really fell in love with the policy side of things. After the internship, there was an opening in Senator Kerry’s Boston office to work specifically on disability issues with one of his staffers. They invited me to do that. So, throughout my entire school year I worked in his Boston office. It’s completely different, because it’s much more focused on his constituents. But I really loved that, because you get to talk to people on an individual basis.” Beth rode the T by herself from Harvard Square to the Senator’s office near the Massachusetts State House. One day a week, sometimes two. She stayed on the subway and passed the T stop closest to the Senator’s office to avoid a steep hill. She planned for extra time to wheel the additional distance back to the office, avoiding the inaccessible T stops. She signed up for text alerts to get advance notice when elevators broke down. “When I answered phone calls, I recognized a desperation in their voices as they reached out to their Senator, who was all too often their last hope in solving their issues,” Beth said. “It was rewarding to resolve specific disability-related complaints, but some we could not help.” She stayed in touch with Mary in the DC office and joined the Senator and staff for events, including a campaign rally at Boston’s Faneuil Hall for Deval Patrick, soon-to-be Governor of Massachusetts. Coffee, Beth’s new habit, stoked long days of classes and homework, swim practice and meets, plus volunteering for KSNAP and Senator Kerry. Beth’s new major allowed her to create and follow an individualized program. She selected classes relating to health care, a wide field of study including economics, regulations, inequalities, public opinion, politics, quality control, and buzzwords like adverse selection and moral hazard. She looked forward to classes at two graduate schools. “I explored health care policy and disability issues with courses at Harvard’s Kennedy School and Law School.” They were her favorite classes. Next: A Big Decision! Over a long August weekend, John and I met Beth at the San Antonio airport for our first trip to Texas. Oppressive heat welcomed us. I bothered Beth with temperature checks and wondered who had the idea for a swim meet in Texas in August. Between prelims and finals of the U.S. Paralympics meet, I left a trail of sweat through the River Walk and the Alamo, monitoring Beth’s temperature often. John’s camera captured butterflies on bright flowers, thriving in the stifling heat.

Beth and the other National Team swimmers learned about lactate testing, an important element of competitive swimming. Lactate increased in arm and leg muscles during races, a potential problem if the athlete had another event in the same session. A quick poke for a drop of blood right after her first race revealed Beth's lactate level. After she warmed down with leisurely laps, a coach tested her blood again. If her lactate level was not low enough, she swam slowly for a longer time. Through this process, repeated after other races, they determined the optimum warm down for each swimmer, so muscles would be at peak performance for the next race. Beth’s swim times in San Antonio earned her a place on the World Championship team going to South Africa. Unwilling to miss a month of college, she gave up her slot immediately to allow someone else to go in her place. However, the Beijing Paralympics would not be declined. Her IPC World Rankings rose to fourth and fifth with the 100 and 200 freestyle. As she finished her internship on Capitol Hill, Beth decided Washington, DC was her favorite big city. Losing the last remnants of her shyness, Beth accepted her first dates. She didn’t see her disability or her wheelchair as impediments to dating. She thought about how her next years would revolve around finishing at Harvard and starting graduate school, so at her request, we sold her car to a Toledo friend who needed the hand controls. I would always cherish our fun road trip memories in her little blue car. Next: Career Change! Beth’s day on the Senate floor during the stem cell debate included conversations with Senator Ted Kennedy and others. She loved every minute.

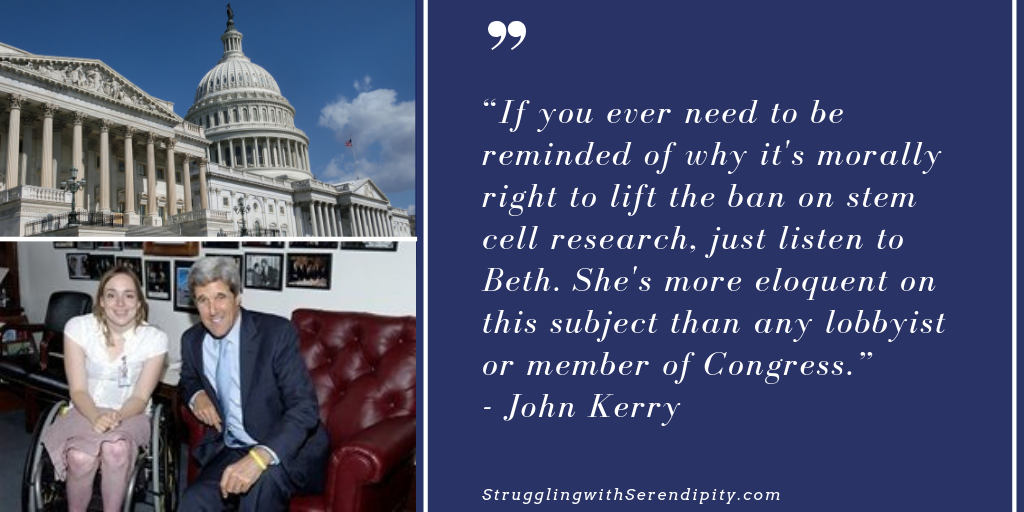

“If you ever need to be reminded of why it's morally right to lift the ban on stem cell research, just listen to Beth,” Senator John Kerry said. “She's more eloquent on this subject than any lobbyist or member of Congress.” When Senator Kerry spoke at the podium on the Senate floor to his colleagues, he introduced Beth and shared her story. He said she served as a “silent, powerful reminder of what is at stake here.” He also signed the paper copy of his speech for her to keep. Newspapers covered Beth’s story in Boston, Toledo, Tiffin, and Washington, DC. John collected them all. “As her Dad, I’m just intensely proud of her,” John said. “She’s a courageous young lady. How many 20-year-olds spent the day on the floor of the U.S. Senate tracking an issue that’s so important to them?” The Boston Globe printed my quote: “She’s not someone who is focused on the cure. She’s very much living her life today. We’re all hoping that stem cell research will offer her more options in the future, but in the meantime, she’s making the most of everything she has.” The Senate passed the stem cell bill with the support of Nancy Reagan and other Republicans. Regardless, President George W. Bush vetoed it the next day, benching the issue for three years until the next president ended the federal limits on stem cell research. Research undoubtedly paved the way for significant improvements in treating many conditions. However, a complete cure for the unlucky quads (like Beth) with a cut spinal cord in the neck AND an old injury? Not likely in my lifetime. We followed Laraine’s advice to not be the first in line for a cure. We knew people who paid a fortune for stem cell treatments in other countries, with little or no results. I thought it best that Beth’s heart wasn’t set on walking again. Even so, I hoped stem cells would make her life easier one day. Next: San Antonio! Washington, DC was unfamiliar to Beth during her first extended stay as a summer intern. One day, she wheeled through an unfamiliar part of the city to meet a friend for dinner. Approaching an overpass by herself, armed only with her gift for minimizing obstacles, Beth increased her speed. She made it halfway up the hill to an even steeper incline. With no tilt guards to prevent the wheelchair from tipping backward, she leaned forward, turned the big wheels toward the road at a 90º angle, and stopped. She wore wheelchair gloves with her fingers exposed for a better grip.

If she reversed her course to go back down the hill, she’d burn her fingers on the big wheels trying to slow her speed and might lose control of the wheelchair. Going up the hill the rest of the way wasn’t a good option, especially without a “running” start. The overpass had two lanes of traffic in each direction, with no parking lane, bike path, or extra space for a car to pull over. Beth decided to go back down the hill and find a subway stop, when a young man stopped his car right in the lane next to her. He put on his flashers, and quickly pushed her up the hill. She realized he was deaf when she thanked him. After dinner, she avoided the overpass by taking the Metro home. Over the July 4th weekend, I drove eight hours with John and Maria from Ohio to Washington, DC, to visit Beth. I bought tickets for a play at the Kennedy Center for the first time. My girls and I loved the musical, Little Women. For the July 4th parade, we congregated by a curb on Constitution Avenue in blistering heat. Beth and I took a break in air conditioning at the Smithsonian American History Museum nearby. Many ethnic groups danced in vibrant costumes. Notably missing? The county fair royalty, tractors, and other farm equipment in Tiffin parades. Senator Kerry’s office manager arranged for Beth to sit next to him at the intern luncheon. Meeting him for the first time, my daughter asked him about the upcoming Senate vote to allow federal funding for new stem cell lines. “I asked him if I could be on the (Senate) floor with him,” Beth told The Boston Globe. “I hope that as the senators are voting they can see a face that reminds them of what they’re actually voting for.” “As a person in the disability community,” Beth continued, “I’ve met so many people whose main goal is just to get better, and stem cell research is their one opportunity to find a cure.” When Beth told me on the phone about her big ask, I realized that the shy, quiet girl she’d been before her injury had been left behind, for good. Senator Kerry not only agreed to her request, he decided to include Beth in his stem cell speech. He requested and received special permission for “privileges of the floor” so she could join him in the Senate on July 18th. Next: An Amazing Day! |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed