|

My daughter Beth’s last race as a member of Team USA was at the Beijing Paralympics, in the same Water Cube where Michael Phelps earned eight gold medals. Beth dropped three seconds off her previous best time in the 50 free to set a new American Record at 1:10:55, even faster than I had hoped.

The top S3 women in the world clocked in at finals from 0:57 to 1:18. At this elite level of competition, the broad variation of 21 seconds starkly contrasted to other finals races at the Paralympics where times varied by seconds or fractions of seconds. The lower-numbered classifications, like Beth’s, tended to include a wide range of function, compared to higher-numbered classifications with specific criteria that more effectively leveled the playing field. I admired how Beth and Peggy graciously accepted the inequities and aimed for achieving her ultimate American Record. “I was so psyched to see Beth at this level of competition,” Brittany said. “I knew how seriously she took swimming, but I didn't have a sense of the enormity of her accomplishment until I was in the Water Cube, donning my handmade 'Go Beth' T-shirt, screaming as she tore down the lane. Watching her swim, I was so proud of her, thinking about how insane it was that one of my best friends is fifth in the world in swimming!” Beth celebrated the accomplishment, happy with her three-second drop and new American Record, as well as her jump in the world rankings from 10th to fifth. Peggy and Beth continued with their post-meet ice cream tradition, though their only choice was the soft serve at McDonalds in the Athlete Village. U.S. Paralympics Swimming won the official gold medal count, with lifetime bests in over 90 percent of their swims despite tough competition from China, Great Britain, and Australia. When the last finals race at the Water Cube ended, USA swimmers had two days for sightseeing in Beijing, a sprawling city of over 6,000 square miles. Next week: Look for my 3rd Serendipity Newsletter!

4 Comments

(This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

A surprising event highlighted our spring. On college teams, athletes with any kind of disability were very rare. After her freshman year, Beth hoped to continue as manager of the swim team with the privilege of practicing with members twice a week. Instead, Coach Morawski asked her to be an official member on the roster of the Harvard Women’s Swimming and Diving team. The invitation was a gift she hadn’t expected, serendipity in its purest form. All the more treasured because she would be the first member of the team with a visible disability. The first quadriplegic. The first wheelchair user. “As a swimmer with a disability going into a Division 1 school,” Beth said, “I didn't know how I would be welcomed because I am not going to be able to score points.” “We were not sure how it was going to work.” Coach Morawski told a reporter from the NCAA Champions magazine. “Everyone is absolutely impressed by her.” Elated, Beth added, “I had no idea Harvard would accept someone with a fairly severe physical disability on the team.” Only Beth could refer to quadriplegia as fairly severe! As tulips bloomed randomly in Harvard Yard, I talked to Beth on the phone about every other day and we met each week for lunch. We’d split a turkey sandwich and two small chocolate desserts at our favorite spot, Finale. After, we stopped at the Brattle Square Florist where I bought a few sunflowers, her favorite flower. She kept them in a vase on her desk. Rakhi surprised Beth with a small birthday party at Finale with a beautiful chocolate cake. Soon after, Beth’s best friends from high school visited with one of their moms. Ellen and Lizzy camped out in Beth’s dorm room while the mom stayed with me in my apartment. We all watched Beth practice at Blodgett before exploring Boston. We walked the Freedom Trail to the Holocaust Memorial and headed to the Prudential Center. We rode the elevator past the expensive Skywalk viewing level and stopped at the Top of the Hub restaurant on the fifty-second floor, to admire the sunset. Glass walls offered a beautiful panoramic view. On a budget, we sat at a table in the bar instead of ordering pricey food at the restaurant. Underage, the three girls drank sodas and we shared a plate of cookies. Lizzy amazed us by pointing out landmarks and neighborhoods in every direction, even though it was her first time in Boston. Next: Swim Trips to Michigan and England! (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

My main reason to live off-campus in Cambridge? To be available for any kind of transition support. To make sure Beth was okay. We agreed I’d have a lot of free time, so I stressed about where to apply for a job. Beth asked me to go with her the first time she swam at Harvard's Blodgett pool. She didn't know what obstacles she might encounter. I saw many challenges. The walk over the Charles River on the Anderson Memorial bridge was impossible in any kind of wheelchair because of the very high and steep curb cuts. Beth pointed out that she could wheel in the street when she was by herself, even though aggressive drivers filled the narrow lanes and turned over crosswalks. She also could avoid the bridge by calling ahead for an accessible shuttle to drop her off at the sidewalk in front of the pool. From the sidewalk to the building entrance: a significant downward slope. Heavy doors to open. Crowded lanes during the open swim. A pool chair lift was temporarily out of service. In the locker room, Beth tried to put on a swim cap, as always. She could get it mostly on, but when it bunched at the top, she pulled it off and handed it to me. I lowered her from the wheelchair to the pool deck and set her mesh equipment bag next to her with her printed workout from Peggy and goggles. I retreated to the stands to watch her swim. She stopped at times to put on hand paddles or a tempo trainer from the mesh bag, or to move for another swimmer in the lane. It wasn't easy sharing a lane with strangers, and she finished the workout early after a half hour. The corners of the pool included a much higher side, so she couldn't get herself out the usual way. Instead, she put her back to the side edge, put both hands up behind her, and lifted herself out of the pool after several tries to sit on the deck. I checked with Beth and she reluctantly agreed for me to ask one of the life guards to lift her knees while I lifted her upper body to her wheelchair. In the locker room, no shower bench meant showering in her chair (minus the cushion), not a good thing for wheel bearings. Changing clothes in her wheelchair created the biggest challenge. One task she had mastered in high school was sliding on sweatpants over a wet suit, but at college, she would have classes after swim practice some days. I sat nearby as she pulled off the wet suit inch by inch, dried off, and tackled underwear and jeans. She let me help when the jeans bunched up under her and she needed to give her arms a break. When we left the building, the slope back up to the sidewalk was not gradual. She could wheel it very slowly, but that day she let me help with my hand on one of the push handles. At Bertucci's in the square, Beth ordered a margherita pizza and talked about the pool, happy that swimming at Blodgett was doable on her own. I returned her smile, grateful for her extraordinary perspective. (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

Beth’s excitement grew with speaking engagements in Toledo and Tiffin plus interviews for two newspapers. She started a Road to Athens journal with her top three goals for the Greece Paralympics. “First, swim my best and feel good about races. Second, swim in finals one night. Third, have fun with the U.S. team.” The newspaper articles about Beth focused on inspiration, a label she disliked. In her mind, she lived her life the only way she could. In my mind, the word “inspiration” meant different things, some good and some not-so-good. At its best, inspiration motivates in positive ways. At its worst, it insults and exploits. What label would reporters choose if more people with disabilities had a fighting chance, with better support, education, and opportunities? With the Paralympics approaching in September, school schedules would keep the rest of my family home. I researched expensive overseas flights to Greece, as well as hotels. The last hectic month of high school barreled by. For prom, Beth wore a blue chiffon dress that fell below her knees. She sat in her wheelchair with the ends of long ribbons tucked under to avoid a tangle in the wheels. Maria styled her sister’s hair into a fancy "do" with small, shiny barrettes. Beth, Ellen, and Lizzy pretended to be ultra-serious models as they posed for silly pictures before the dance. High school ended in an anti-climactic way, with more important things ahead. At graduation, Beth wheeled up a ramp to the stage at the stadium and spoke to the crowd as one of four valedictorians in the class of 226 students. Ellen, also a valedictorian, gave a speech about how others change our lives. It reminded me of Beth and the song For Good, my favorite from the musical Wicked. On a whim, I bought tickets to see Wicked on Broadway later in the summer with my girls, and planned a road trip to New York City. None of us had ever been to The Big Apple. Another first—one that would establish a new favorite destination. Next: Graduation Celebrations! (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.)

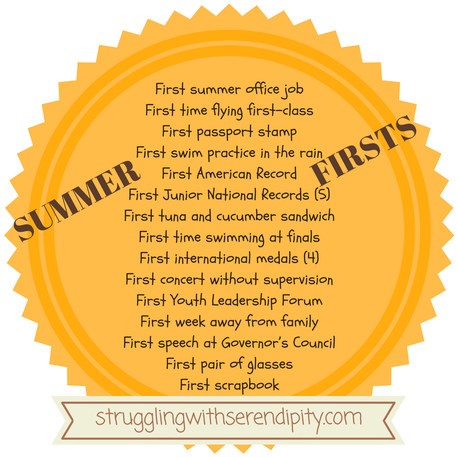

My initial expectations about Beth’s spinal cord injury proved wrong, in spite of my work experience with disabilities. At a Toledo Raptors fundraiser at the zoo, I spoke with a lovely friend with multiple sclerosis. As we chatted, I remembered our first meeting a few months after the car accident. Then, I judged everyone by their disability, certain that quadriplegia won the ‘worst disability’ contest. I thought that nothing could be as awful as a complete, or nearly complete, spinal cord injury in the neck. I stubbornly clung to that misconception, weighing one disability against another. Through the first years, my view gradually shifted until I compared my earlier notion to a blind person judging a swimsuit contest. Everyone’s lives shared the essence of an iceberg, not just quads. What we couldn’t see under the surface always mattered. One person’s heaven could be another’s hell—with or without a disability. Beth volunteered for WaterWorks in Toledo for the second year in a row, helping children with a disability learn how to swim. At one session, she talked to a group of preschool children before getting in the water with them, not surprised by blunt questions. A little boy asked, “How do you sleep in your wheelchair?” He didn’t look convinced by her answer. In early April, Beth blew out eighteen candles on a chocolate cake. Around our kitchen table, Ellen and Lizzy sang happy birthday with John, Maria, and me. I wondered what Beth wished for. Always skeptical of quad-friendly gadgets, she unwrapped a small present from me, a curved plastic tool, and rolled her eyes as only a teenager could. When I explained what it was, she agreed that opening a soda can with the curved tool would be better than using her teeth. Even so, she chose a different solution. Practice more—and more—until her hands could do the trick. Next: Spring Cleaning on Steroids (at the group home) and Senioritis!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) Managing the group home escalated my headache with less sleep and a full dance card. The base level of pain had gradually increased over a dozen years. How bad would it get? Over-the-counter medications didn’t make a dent. When I tried an opiate after surgery, I felt worse, not better. A prescription anti-inflammatory muted the headache—and increased my stroke risk. I read a study about how the brain gets wired to frequent pain signals, making it difficult to break the cycle. Obviously. I made a concerted effort to stay positive and suppress my fears of higher pain. At home, I kept up with Beth and drove her to swim practices on my evenings off. She took on new roles, unafraid, including the top job of news editor of the school newspaper, The Tiffinian. A feature in the paper titled Senior Superlatives reported on a class election that voted her most likely to be President and most likely to be rich. “I didn't want both so I gave the rich title away,” Beth said, with a laugh. The votes of her classmates also put her on the Homecoming Court, surprising her. “I was shy in high school,” Beth said. “I had more fun than most, but I wasn't a cool kid.” The night of the Homecoming football game, the Court arrived at the stadium in convertibles before lining up on the track to be presented to the crowd. A problem we didn’t anticipate handed Beth a rare defeat. “I wheeled myself everywhere, but my escort wanted to push my chair across the field,” she said, while also admitting the bumpy turf was difficult. It was a standoff on the 50-yard line, her escort equally as stubborn as Beth. She reluctantly gave in. “But I kept my hands on the wheels and pushed myself at the same time!” When the pageantry ended, Beth sat with her best friends on the platform in the student section to watch the game. Ellen and Lizzy gave her a bouquet of flowers and an adorable present. They made a Build-A-Bear and dressed it up with a fancy dress, homecoming crown, magic wand, and queen banner. They had been sure Beth would win. She didn’t, and hadn’t expected to. But... The queen bear was a sweet reminder of friends always in your corner. (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) I stopped counseling since I was perfectly fine. After all, I finally made progress in the wake of three years of weekly sessions. Guilt and anxiety no longer dominated my days, which felt like a monumental gift. I scheduled dentist appointments to fix my second cracked molar, casualties of teeth clenching—despite the biteplate I wore each night. My doctor added a temporary muscle relaxant at bedtime to reduce the clenching. A high dose of Celebrex usually tempered the headache and kept me moving. I watched Beth hold a pen awkwardly in her right fist, not hesitating as she wrote her motto on a Challenged Athletes application. ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE. She wholeheartedly believed the motto was true. And it really was, though only for her and a small percentage of other people with her priceless perspective. Those with and without a disability. I filed away a note to myself that said, “Anything is possible, except when it’s not.” I intended to write about how she dismissed all she couldn’t do as irrelevant. “I think walking is over-rated,” Beth said, with a smile. Unable to stand and not focused on a far-off cure for quadriplegia, she continued to work hard to defy the usual limits of quad hands. Her spinal cord injury erased normal finger function. Even so, she wouldn’t write off any fine-motor tasks she really wanted to do. One example of many: putting her hair up in a ponytail after trying several times a day for two years. A tribute to unwavering belief and persistence. As Beth's last year of high school started, she quietly completed an early admission application to Harvard, convinced it was a long shot. “I didn’t tell anyone since I didn’t think I would get in,” she said. If someone asked about college plans, Beth mentioned the University of Michigan, one of the colleges she planned to apply to after she heard back from Harvard in December. NEXT: A new job!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) College applications covered our kitchen table before Beth’s senior year of high school began. She questioned the need for help at college her freshman year and wondered if I could live off-campus instead of in the dorm with her. Separate housing for me for any amount of time would add costs on top of her out-of-state tuition, room, and board. High college expenses seemed certain. John and I decided not to hold her back because of finances. We owned the Tiffin house and planned to borrow off it. My second counselor moved away and the third nudged me forward. After nearly three years of weekly sessions, I had few tears left. I had been spinning in a rut, perseverating on my choices the night of Beth’s injury. As if I had a replay option. The new psychologist told me the accident could not have happened any other way. She framed it as less of a colossal failure and more of a perfect storm of events. I woke up very early that morning to set up a refreshment stand for the choir contest. John stayed home to study for his National Board test. The night of the accident, the OSU concert ran longer than expected. The psychologist’s next point hit home: I could not make a good decision (i.e., calling John on the pay phone), because exhaustion impaired my judgment. That fact somehow flipped a switch for me and allowed a measure of forgiveness. However, no amount of reasoning would be enough, if Beth had been unhappy. I gradually reduced my zoloft to a lower dose. As always, my headache tightrope remained, a precarious and somewhat mysterious balancing act to keep the level manageable. At home, Beth gathered summer mementos and made colorful collages with a small paper cutter. She used markers to add descriptions and funny comments on each page, approximating the calligraphy style she learned before her injury. She created a tribute to the magical summer in her first scrapbook. The last page listed 15 notable summer firsts, including her first US Paralympics American Record, her first passport stamp, her first tuna fish and cucumber sandwich, her first concert without a parent, and her first swim practice in the rain. Beth’s very best ‘first’ of the summer: wheeling around Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) The highlight of Beth’s summer: the Youth Leadership Forum of the Ohio Governor's Council on People with Disabilities. Students with a disability in their junior year of high school had applied to attend as delegates. Five days without parents would be a first for Beth and others, with personal care assistants available for those who needed help. I dropped Beth off at a fancy hotel in Columbus. I kept my phone charged and the gas tank filled, available at a moments notice. I could hardly wait to pick her up, even though she called every day and sounded happy on the phone. I kept busy, painting a bedroom with John. Maria and I went shopping and to Taco Bell in between her jobs. I met an old friend for breakfast. John and I spent a leisurely day in Findlay. We shopped, held hands at a movie, and ordered ginger chicken at our favorite restaurant. Still, I thought about Beth often. I worried that she would be reluctant to request help and get frustrated. I was right about asking for help, but wrong about her response. Driving home with me to Tiffin, Beth said, “It was the best week of my life!” I smiled, glad to hear it but hoping many others would be even better. The first night of the forum, she asked for help to get up on the higher hotel mattress. The other days, she figured out how to do it herself. She set her alarm early and worked to shower and dress completely on her own, allowing for extra minutes to zip zippers and button buttons. Proud that she could. After difficult but independent transfers, she even un-bunched her jeans by herself. Introduced to disability issues past and present, large and small, Beth learned about the fight for the Americans with Disabilities Act. The speakers discussed stereotypes and why many people with a disability did not have a job. Advocates talked about limiting Ohio’s handicapped parking permits to those who needed them the most. One session explored ramifications of denied access and how to work for change. Information mixed with social events. “The staff was great and there were a number of outstanding speakers,” Beth said. “The event had a big impact on my life my first year as a delegate.” The forum anchored Beth to others with a disability. She met delegates, staff, and speakers with epilepsy, cerebral palsy, paraplegia, quadriplegia, dwarfism, learning issues, mental illness, and brain injuries. Some were blind or deaf. She accepted an invitation to report on the Youth Leadership Forum at the annual meeting of the Ohio Governor’s Council on People with Disabilities. “The Ohio forum proved to me that the disability community is widely diverse and vitally important.” Next destination of a non-stop summer: Edmonton, Alberta!  (This blog tells my family's story. To see more, click "blog" at the top of this webpage.) On a free day, Beth suggested the Mohegan Sun casino to see the immense works of art. Wheeling through massive spaces, she realized at one point that we had accidentally entered a restricted area for adults eighteen and over. With slot machines nearby, Beth, seventeen, asked to try the poker slots. I put quarters in the machine and let her tell me which cards to keep. She never touched the slots and helped me lose $30. I took photographs at every destination while Beth collected menus and flyers and other small things for a scrapbook she planned to make. She found one she liked at a shop in the historic bridge district in Mystic, Connecticut. Equally exciting, we found the fifth Harry Potter book, The Order of the Phoenix, to add to her collection, one of the five million copies bought in the first 24 hours. Beth’s happiness was contagious. We ate lunch at Mystic Pizza, famous for the 1988 movie with the same name. I helped her scoot out of her chair to a seat in a booth. Memorabilia decorated every nook and cranny at the restaurant and Beth rated it the best pizza, ever. I bought her “A Slice of Heaven” T-shirt. We sat on the waterfront of Mystic’s picturesque harbor on a flawless afternoon. An easy travel buddy, Beth appreciated everything under the sun. She tilted her face upward, closed her eyes, and smiled. I wrapped her in a big bear hug. She patted my back with her right hand, a habit from her toddler days. Knowing how suddenly bad things could happen, I would never take joy for granted. I embraced the singular moment while a new realization dawned. My guilt for causing her injury was self-imposed and no one, least of all Beth, blamed me. Junior Nationals ended with a dinner and dance in a large packed ballroom. When loud music started, hundreds of kids with every kind of physical disability danced standing up, sitting in a wheelchair, or break dancing on the floor. With no one different and no one the same, they all shined in that snapshot of time. Beth danced carefree in the middle of it all. Next destination of a non-stop summer: Cambridge, Massachusetts! |

Cindy KolbeSign up for my Just Keep Swimming Newsletter by typing your email address in the box. Thanks!Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed